Beyond the Frame 85/

Can a camera change how a child sees the world? In teaching photography to children, I discovered the most important lessons weren’t about pictures at all.

Teaching photography to kids

I’ve taught photography to hundreds of adults, in classes and workshops. But when it comes to teaching photography to children, I’m often the one who ends up learning the most.

Seedlight

The Seedlight project came about, as all the best things do, from a moment of serendipity – and from meeting one child in particular, Hayat, who I will introduce later on.

In 2010 and 2011, my time was divided between assignments for NGOs and teaching adult photography workshops. Many of my NGO clients work on projects benefitting children from disadvantaged backgrounds. I often share photos with the kids, either by scrolling through frames on the camera’s LCD screen or by making instant photos to hand out. The kids also enjoy using my cameras to make their own photos of their friends and classmates.

I recognise how much enjoyment children get from playing with cameras, and how proud they are to share their pictures with friends. What if I brought photography workshops into the NGO projects I was documenting?

And so the Seedlight project was born.

With contributions from generous family and friends, I buy 24 point-and-shoot digital cameras and tag a week or two onto the end of an assignment. Working with the NGOs, we distribute cameras to the children and set up easy-to-follow photography lessons.

I’ve taken the project to Cambodia, Nepal, Bangladesh, Thailand, Kenya and Ethiopia.

It’s a simple premise. We help the kids learn basic photography skills. The cameras are donated for them to keep. They use them at school and take them home, documenting whatever appeals to them.

We print the photos and the children select their favourites, which they compile into an exhibition in their school or orphanage, for friends and family to admire.

We try to keep the process as straightforward as possible and place very few restrictions on the children. It’s an opportunity for them to explore and express themselves through a creative endeavour.

The NGOs I work with are often small and work with very modest funding. Staff work hard to provide food, clothing and essential medicines. Artistic pursuits are a luxury that the children are rarely afforded and photography is, understandably, not a priority. But I know that a camera can be a liberating tool, bringing confidence where it is sometimes hard won.

Addis Ababa

I’m sharing short descriptions and photos from four of the children, residents at an orphanage in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. I hope they will give a sense of what the children get out of the experience. And I hope you will enjoy seeing the kids’ photos as much as I know they enjoyed making them.

Yohannes

“He speaks through his eyes”, was what one of his friends told me when I first met Yohannes. What better trait for an artist?

Yohannes is one of life’s natural observers. He’s friendly but rarely the centre of attention, often found caring for the pigeons that roost in an abandoned cupboard at the far end of the orphanage playground.

Putting a camera into Yohannes’ hands produced a perfect illustration of the project’s aims. Providing him with a new way of interacting with the world allowed him to express himself creatively, without the tiresome demands of having to speak.

The camera allowed the rest of us to see the world through Yohannes’ eyes. A world of quiet, unhurried observation. An uninteresting shelf of threadbare shoes becomes a study of bold lines and earthy textures. We watch a boy playing with a ball, Yohannes sees the shadow on the wall.

During our first lesson, Yohannes picked up my cumbersome camera with his right hand, called a white pigeon to perch on his outstretched left, instinctively shifted to frame the bird against a blue wall, put his eye to the camera, framed, and clicked. The resulting image remains one of my favourites. The memory of that moment, likewise.

Yohannes taught me far more than I could ever teach him. He reminded me of the power of patience, that observation and anticipation are the keys to unlocking memorable moments. When I grow up, I want to be like Yohannes.

Hayat

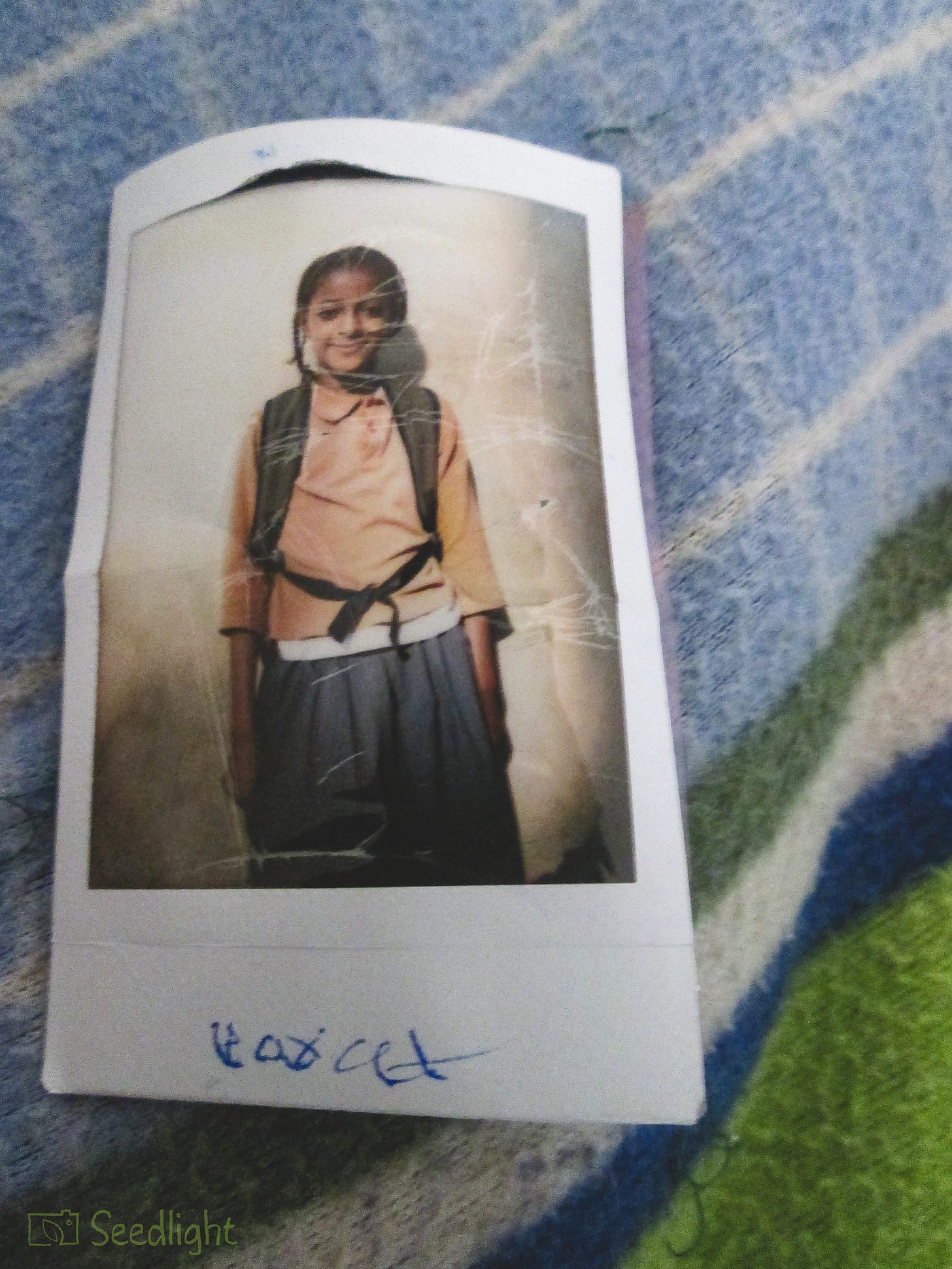

The Seedlight project was inspired by my first meeting with Hayat. She is the reason these images exist.

You would not guess that Hayat has suffered more physical and emotional distress than anybody should endure in one lifetime, let alone before their 8th birthday. She has a ready laugh, loves the company of her friends, and is rightly proud of her photographs.

When we reviewed her images on a laptop, she picked her favourites. She loves this photo, taken through the window of a moving bus. Three shiny, pink ballgowns in a shop window.

Hayat instinctively understands chiaroscuro lighting – the use of strong contrast to create depth and volume. Without instruction, she finds it when photographing the orphanage staff.

Another of Hayat’s favourite images is, at first glance, an unremarkable photo of a dog-eared instant photo that I gave her at our first meeting. Touchingly, Hayat kept her instant print under her pillow.

I asked why she chose this photo as one of her favourites.

“It’s the first time I saw a photo of myself,” she replied. “And the first time I saw you and you saw me.”

Hayat taught me that giving cameras to kids is fine in itself, but the real value comes from the connections made from giving one’s attention fully to another person.

When I look again at Hayat looking out from the faded, folded instant photo, I see a young woman who wants nothing more in the world than to be truly seen.

And perhaps, one day, a reason to wear a shiny, pink ballgown.

Rahel

Like all the best documentary photographers, Rahel might not be the most obvious person in a crowd. But she will have seen you. She will probably have photographed you too. Quietly and respectfully, Rahel makes photos in a considered way, patiently waiting for the right moment to capture the subjects which interest her most.

Rahel loves to photograph her friends. Her deal is that she’ll paint your nails if you pose for a portrait. What people may not realise is that Rahel loves painting nails just as much as she loves photography. For Rahel, it’s a win-win.

Rahel reminded me of the importance of subjectivity, and how the images we see affect each of us differently. When picking her favourite photos, Rahel selected a blurry, out-of-focus picture of another girl. I gently asked whether she might not prefer to choose a sharper photo of a different subject. The question seemed to puzzle her. She looked me in the eye and said, “But this is my best friend!”

Sharp focus and accurate exposures are admirable, but we ought not to forget Rahel’s lesson: Content is King – or Queen.

Kesahun

What he lacks in age and physical size, Kesahun more than makes up for with eager, wide-eyed determination. Kesahun is a force of nature.

When it was suggested that a five year-old would make a good photography student, I had some doubts. That was before I met him. We always know when Kesahun has arrived. He won’t be ignored, even if he has to climb on your head, pull your ears and poke you in the eyes to get your attention. If Kesahun wants you to look at him, he doesn’t wait, he simply twists your head in his direction. Kesahun has important things to share and he wants to say them without delay.

We regularly print the children’s photos and spread them on a desk. All the other children sit on chairs or stand beside the table, organising their pictures in order of preference. Not Kesahun. He climbs onto the table, sits cross-legged and spreads the prints around him. He doesn’t so much carry out an edit as he becomes a part of it.

Our first and pretty much only photography lesson lasted no more than 30 seconds. I demonstrated turning the camera on, looking into the viewfinder and pressing the shutter button. Kesahun nodded, walked off with his camera to the front gate of the orphanage, made a photo of the security guard, sauntered back, showed me the photo as evidence that he was all sorted, thank you, and promptly ran off to begin his photographic adventures.

By the end of the first week, the camera case permanently attached to his belt looks like it has been through several wars. Yet the camera inside is spotlessly clean. Several times each day he carefully cleans the screen and tiny lens with a tissue. When he sees me cleaning my camera with a favourite cotton cloth that I’d bought in India, he held out his hand. It wasn’t a childish demand from a five year-old. He was simply letting me know that he needed that cloth more than I did. And he was right.

Kesahun leaves nothing to chance. He photographs everything. Yet for all the joyful energy and enthusiasm, there are more thoughtful photos too. A flowing wave of red ribbon on blue fabric. A wide framing of a friend in pink Crocs and blue dungarees. I doubt Kesahun will ever sit still long enough for me to teach him about the theory of negative space. But, evidently, it’s not a lesson he needs to hear.

Occasionally, if I’m ever hesitant about how to approach a subject, I’ll think of Kesahun and be inspired by his bold, no-nonsense approach. If, like Kesahun, we have something important to share, why wait?

Lessons learned

When I began the Seedlight project, I hoped it would offer some creative opportunities to the children and a little respite for the hard-working NGO staff.

It’s true that cameras offer a means of expression, allowing children to share the things that are important to them. Cameras can give a sense of self-worth, a way to be the director of their own narrative, something that many of these kids have rarely enjoyed.

A camera is a tool of empowerment. Giving a camera to a child permits them to believe, “I am worthy of this”.

I’ve always found the experience of teaching photography to children enormously rewarding. I’ve watched them grow in confidence with a camera in their hands. A camera gives a reason to be where they want to be, to engage with what they find most fascinating. That’s pretty much why I carry a camera, so I can relate to that feeling.

And I have learned so much more than I’ve taught. I’ve been reminded of the simple joy of making photographs, that technical considerations can be a distraction, that our connection to a subject is always the most crucial thing.

To photograph with a sense of childlike enthusiasm and wonder is, I believe, an aspiration worth holding on to.

“Only those who look with the eyes of children

can lose themselves in the object of their wonder.”

– Eberhard Arnold

Beyond the Frame Recommendations

Articles, documentaries, exhibitions, podcasts and more.

☆ Read – Goats and Soda

Stephanie Sinclair is the founder of the NGO Too Young to Wed, advocating for and raising awareness of the plight of child brides.

Providing cameras to ten girls rescued from child marriage for one week proved to be a profound experience.

“Today, they gave us small things called cameras. Everybody carries them. For the rest of my life, I will not forget this day.”

– Modestar

The NPR article describes how cameras provided the girls with a means of creative exploration and artistic expression which worked as art therapy.

▶︎ Watch – Camera Kids

I’ve seen trailers for this documentary about a project that provided cameras and tuition to 19 Rwandan children, orphaned by the 1994 genocide.

David Jiranek, founded Through the Eyes of Children, which has recently celebrated its 25th anniversary.

I’ve also found a PBS interview with the filmmaker, Beth Murphy, and a Time article about the project.

I’m waiting to hear back from the producers with more details of where to find the film, but even the trailer offers a powerful glimpse into how photography helped orphaned survivors.

◉ Listen – Interview with Wendy Ewald

A really interesting conversation with Wendy Ewald, a pioneer who created several collaborative projects working with children. Wendy’s most well-known project is Portraits and Dreams, photographs and Stories by children of the Appalachians.

⦿ Learn

Finally, as we’re talking about photography and children, a reminder that the Child Protection Policy provided by Ethical Storytelling incorporates UNICEF’s Principles for Ethical Reporting on Children. The policy is available to download for free and recommended reading for anybody involved in photographing children, especially those who are living amidst crisis.

✤ Create

A series of creative prompts, inspired by Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies, and designed with photographers in mind.

Read more about the concept and learn how to use my Oblique Strategies for Photographers.

And finally…

What do you think of the children’s pictures? I know my appreciation is coloured by time spent in the kids’ company, which is always a privilege.

Do the images reveal something about the lives of the children who made them? I’m interested to know what you think and would appreciate your comments.

I hope that whatever you’re doing this week, you’ll find time to escape the doom and gloom news cycle. It’s important to be well-informed, of course, but we also need time to focus on what’s good in the world.

Until next time, go well.

Wonderful project Gavin. I love the 'I see you, you see me' aspect. It's obvious on one level, and profound and moving - us seeing one another is what makes connection, empathy and community. Did I miss the part where we can donate to the project? Please provide!

Beautiful initiative