Beyond the Frame 20/

Focal lengths. What are they and how do we use them? With examples from India and Thailand.

Focal Lengths

Following on from last week, Monica asked what factors influence my choice of focal lengths. It’s an excellent question.

It’s safe to assume that most of us know what focal length is but here’s my simplified definition so we’re all on the same page. The focal length, given in millimetres, indicates a lens’s angle of view — or, more correctly, field of view. A lens with a low number such as 16mm or 24mm has a wide field of view. A high number, such as 135mm or 200mm indicates a much narrower field of view.

I won’t go into the mechanics of focal length calculations. There’s a Wikipedia page if you really want to know the mathematics but I can’t promise it will help.

A quick example

Here’s a picture of Grand Central Station in Manhattan. If I was to remain in exactly the same position, fix my camera to a tripod and attach lenses with different focal lengths, the camera would “see” the field of view indicated by the coloured rectangles.

With a 16mm lens, I get a very wide view and the clock above the Information kiosk is very small in the frame.

As I attach lenses with longer focal lengths, the angle of view narrows and the clock appears larger and larger in the frame.

At 200mm, the camera sees very little of the wider station concourse and the clock becomes very prominent.

There’s a handy tool on Github if you’d like a dynamic example.

You may know that the human eye’s angle of view is approximately 50mm, which is why 50mm lenses are so popular. I found a fascinating article about the Physics of Sight, with an illustration showing different animals’ field of view. But before we get diverted down a rabbit-hole (where our relatively wide 50mm field of view would be redundant), let’s look at some photographs.

Varanasi, India

Here’s a straightforward example from a boat on the Ganges river, shortly after sunrise. I’m in the same position at the boat’s stern for both frames.

With a 16mm lens (above), I can include the oarsman, the boat, both oars and Varanasi waterfront stretching into the distance.

Switching to a 140mm focal length, I can make a close-up portrait. I haven’t moved. Nothing has changed other than the focal length of the lens.

Sadhu and Rainbow Umbrella

Here’s another example of a sadhu (holy man) sitting on the riverbank, reciting mantras beneath a rainbow umbrella. I have a thing about rainbow umbrellas so wasn’t going to walk past this opportunity.

Having exchanged pleasantries and obtained his nodded agreement that I could make some photos, I began with a 16mm focal length, including his surroundings for context.

Sitting beside him, I switch to 28mm for a closer perspective whilst still including some background.

You may notice two things about the picture on the left.

Flare from the sun on the lens created a distracting highlight by the sadhu’s head. Lowering the camera to position the sun behind the umbrella resulted in an awkward perspective so I didn’t pursue that angle.

I’ve photographed enough rainbow umbrellas to know that an optical illusion occurs if both sides of an umbrella are not visible. Instinct tells us that the umbrella curves inwards, it’s obvious. But because we see the umbrella in two-dimensions, it can be ambiguous. It’s also possible to see an outward-curving umbrella, like a satellite dish directed away from the sadhu towards the sun.

A slightly higher viewpoint eliminated the flare and allowed me to include both sides of the umbrella. When it comes to umbrellas, I know things.

As I’m making these small adjustments, the sadhu is concentrating on his prayers, occasionally lifting the book to his forehead as if transferring blessings directly into his mind.

Now I’m using an 85mm focal length, framing the umbrella as a background for a closer portrait. I want to focus on the Sadhu’s hands and his book. I make some frames in landscape format and some in portrait, all at 85mm.

Finally, I stand and make a few more frames from different perspectives to ensure that I’m going away with sufficient variety for an editor to feel spoiled for choice.

Varanasi, the river Ganges, a meditative Sadhu, and a rainbow umbrella. On that day it felt like all my Christmases had come at once.

However, strictly between you and me because you’re a paying subscriber and I appreciate that, I’ll share a secret. There’s something missing…

I’ll tell you what it is — but I’ll warn you first that once you’ve read what’s missing, you’ll forever see these pictures with different eyes. Maybe cast your eyes over them one final time before I alter your opinion of them irreversibly?

Ready?

There’s no eye contact! I was photographing, the Sadhu was chanting, we were both engrossed in our own activity. After our first exchange, he didn’t look up again. That fact didn’t register with me at the time. If it had, I would have waited for him to look up. I wish he had peered at me over the top of his book. But he didn’t, so that’s a picture which only exists in my imagination.

I notice the absence of connection every time I see the photos. Now you will too. 😬

Pete Souza

Former White House photographer and all-round nice guy Pete Souza gives a fascinating insight into his camera gear and lenses in this video.

Notice how Pete talks at length about focal lengths and categorises images by the focal length used. It illustrates how his choice of focal length is pretty much always the first decision made. Note also that he only ever used a flash for official portraits in the Oval Office. Proof that it’s possible to make amazing pictures with natural light alone.

You can follow Pete on Instagram and his book, The West Wing and Beyond showcases a unique collection of images.

On Assignment

My final example comes from a magazine assignment photographing restaurants and the chefs who are using ingredients from the Thai royal family’s organic farming project.

The Restaurant

A wide-angle view provides an overview of the restaurant, gives readers an idea of the ambience and allows me to include the upside-down, neon piano on the ceiling!

The Chef

An 85mm lens is perfect for portraits. This is a Prime lens, not a zoom, which allows it to have a wide aperture / narrow depth-of-field. This throws the food on the table and the wall behind the sofa slightly out of focus, making the chef the focus of our attention.

The Food

Longer focal lengths aren’t only for subjects that are further away. They’re ideal for details and close-ups too.

Summary

Some final thoughts about focal lengths.

Having a variety of focal length lenses in your camera bag is useful but not essential. For my work cameras I have a range from 15mm to 200mm so I can cover all eventualities. When I’m photographing for my own projects, I have a 28mm lens and a 90mm lens and that’s enough.

The temptation is to think of longer focal length lenses as only for photos of far away things. Unless you’re a wildlife or sports photographer, that’s not the case. Different focal lengths produce varying perspectives, as my example of the Varanasi oarsman illustrates.

Prime lenses (with one fixed focal length) typically produce better quality images than zoom lenses. However, the difference in quality is getting harder to discern. So, for versatility, a 24–70mm is hard to beat.

The real benefit of a prime lens is that you’ll become accustomed to the field of view. With practice, you will instinctively know where to position yourself to get the right composition.

Pop Quiz and Prize Time

Now that you know all about focal lengths, a quiz.

What focal lengths were used to make these two images?

I’ll send a copy of Pete Souza’s book, West Wing and Beyond, to the first person who leaves a comment with the correct answer (one guess each). Answers revealed next week.

Analysis

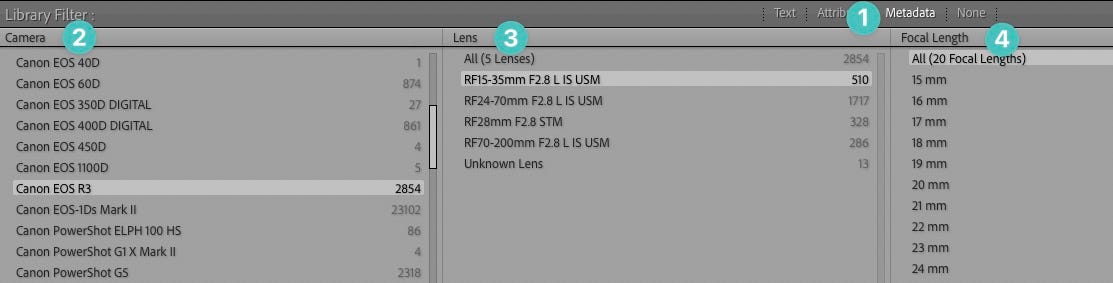

If you’d like to analyse which focal lengths you’re using most often, Lightroom Classic can provide the statistics.

In the Library module select “All Photographs” in the left panel, click on Metadata in the Filter Bar at the top of the window (if the filter bar is hidden, press backslash \ on your keyboard).

A series of columns is revealed. Each one can be set to display a different metadata parameter. In this example, the first column shows a list of cameras.

Change the second column to Lens.

Select “Focal Lengths” in the third column and you’ll see a list together with a number indicating how many images match the criteria.

I’ve used this information to help me decide which lenses to invest in. For example, knowing that I use wide-angle lenses much more often than telephoto lenses helps me spend my budget wisely.

The graph shows the distribution of images across a range of focal lengths. It’s a bit misleading because there are over 150,000 images at 15mm and 100,000+ images at 24mm but allowing the chart to extend that far makes every other column shrink to become virtually invisible.

You don’t need to go to the extent of making a spreadsheet. Lightroom’s filtered metadata list is easy to read. I just like to see a visual representation.

If you enjoy looking at that kind of data, you can change the Lightroom metadata columns to reveal which apertures and shutter speeds you use most often. 😬

I hope our look at focal lengths has been useful. As always, if you have any questions, leave a comment or find me in the Chat. And don’t forget to leave your answer to the quiz question in the comments.

Cheers!

This post felt like all MY Christmases came at once! I’m going to guess 90mm and 200 mm. (But you didn’t answer why you chose 28mm for your walking around lens. Harder to compose well than with 35mm)