Beyond the Frame 60/

Street portraits. How to make the most of an impromptu portrait session with a stranger.

Street Portraits

In the middle-ground between candid street photography – where subjects are usually unaware they’re being photographed – and the intentional, extended, outdoor studio portrait – often with supplementary lighting – lives the Street Portrait.

A street portrait is the result of a quick, impromptu collaboration between photographer and subject, typically using available surroundings and natural light. Street portraits needn’t be made on a street, that’s just shorthand for any public space.

I’ve made a quick selection of street portraits to illustrate the concept.

Each of these portraits began with a few words, a nod, a smile, sometimes just the universal language of a simple gesture, which resulted in a brief alliance between two strangers.

Shiny Things

Khun Anong was walking through the grounds of the Grand Palace in Bangkok when our paths crossed. Her purple clothing and shiny headdress caught my eye. Yes, I am a magpie.

Photographers often speak about their cameras being metaphorical keys that can unlock opportunities and experiences which might otherwise pass by. This has never been more true than with street portraits. In my experience, carrying a camera provides the perfect excuse to approach a stranger and say, “Excuse me, may I take your photo?”

I know this can seem like a daunting prospect, but, providing we employ a modicum of common sense and are courteous, I don’t see it as an imposition. It’s really a compliment. What we’re actually saying is, “There’s something about you that I admire and I’d love to share that with you.”

I caught Khun Anong’s eye and said, “Excuse me. I’m sorry to interrupt you but I wanted to say how great your dress looks against the temple fresco. May I take your photo?”

Khun Anong was more than happy to pose. She lifted a parasol from her bag. “This will look good in a photo”.

She explained that she had been performing traditional Thai dances in the palace. Then she sat and placed brass lep fon fingernail adornments on her hands, posing for another picture. Really, I was only a passenger once our three-minute collaboration had begun.

Without a camera in my hand, I might still have been sufficiently impressed with her costume to speak to Anong but it’s much less likely. The camera provides an imperative. Then it choreographs the dance where two strangers can face and look intently at each other for a few moments.

We tend not to pay compliments to random strangers because … I don’t know … social convention, I suppose. The risk of being misconstrued? It’s a pity. Fortunately, the camera’s magic can dilute embarrassment and overcome pompous etiquette.

The camera gives us an excuse to pay somebody a compliment that they’d love to hear.

The Colour Coincidence

Walking along the chaotically busy Chandni Chowk in Delhi, I saw this young man waiting at a bus stop. I’d be willing to bet that many other people noticed his brilliantly colour-coordinated shirt together with the wall he was casually leaning against. But it’s only because I had a camera in my hand that the evidence of that uncanny synchronicity is here to be shared.

Believe it or not, he claimed not to have noticed the colourful coincidence. When I pointed out the matching colours, he laughed. I asked if he’d be happy for me to make a photo. He smiled and wobbled his head in that typically Indian manner which means OK. I made three photos, showed him the results in the camera’s LCD screen, he smiled again, I thanked him, we shook hands and I went on my way. The whole encounter lasted no more than 60 seconds.

I wonder if he is reminded of that bus stop whenever he wears the green shirt. I know I’ll never forget that tiniest fraction of a lifetime when our paths crossed because I have the picture to remind me.

Coincidentally, two minutes further down the road, at the entrance to the Fateh Puri Masjid, a bright red wall provided a similarly colour-coordinated backdrop for a woman’s shawl. It’s not a street portrait, as such, but I’ve included it because with that degree of serendipity, it would be rude not to.

A respectful street portrait honours a person with whom we share our world. Street portraits are most definitely not about “taking”, they’re about noticing and paying attention.

A street portrait needn’t be – shouldn’t be – a one-sided transaction. The photographer might end up with a picture or two, but I know for sure that the photo quickly becomes secondary to the momentary but meaningful human connection.

In the midst of the hurly-burly of daily life – the bills, traffic, laundry, kids, dental appointments, podcasts, groceries, unread emails, birthdays, cat litter, bin day, leaky pens, group chats, and Post Office queues; a polite stranger taking a moment to tell us, “Hey! I love your hat. May I take your photo?” might seem like it would be just another unwelcome demand. But I know that a request born of an authentic admiration is most often interpreted as the photographer saying, “Hey! I see you.” And the unspoken response is almost always, “Oh! Thank you. I like to be seen.”

The Smile

If you’re making a street portrait, I encourage you to make the most of the opportunity. There can be a temptation to make one quick frame, maybe two, then lower the camera, say a shy “Thank you”, and scurry away before things get too uncomfortable.

Don’t do that. If somebody has been gracious enough to pose for a photo, do them justice. Make two frames, pause, keep the camera steady, look up and re-establish eye contact. In that moment, everything shifts, the stiff pose dissolves into laughter and you will have a chance to make a more engaging image.

I’ve mentioned this seemingly simple strategy before. No doubt I’ll mention it again because it’s the most valuable piece of advice for any kind of portrait. Eye contact is everything. When we raise a camera to look through the viewfinder, we introduce a physical barrier and signal the start of the serious business. If we recognise that and then diffuse it, chances are we’ll make a more memorable image.

The difference between the first frame of the young man in a doorway (above) and the seventh frame (below) is easy to see. In this case, I might favour the first, but it’s easy to tell in which frame he looks more relaxed.

Here’s a street portrait of a man who was only too happy to be given a reason to escape his household chores for a few minutes.

Here’s an example from Indonesia. These are the first four of 12 frames I made of a farmer in a rice paddy. “Street” portraits might be made far from the nearest street!

Do you see the same sequence of expressions that I see?

Frame 1: Slightly unsure but smiling politely

Frame 2: Lips pursed, still polite but not a genuine smile

Pause, lower camera, Eye-contact

Frame 3: Laughing (out of focus), tension dissolved

Frame 4: A genuine smile

Context is everything

A contrasting example where laughter would not have been appropriate.

I met Anupama three days after an earthquake had caused extensive damage and claimed almost 9,000 lives in Nepal. My job was to document the immediate aftermath, the rescue operations, and the plight of those who had lost their homes and livelihoods.

Like many tens of thousands of Nepalese families, Anupama’s home had been destroyed. She and her family had gathered what possessions they could find and were living in the playground of a nearby secondary school. I met them, as I met many families, by accident, as the NGO team I was with searched remote villages.

To look at the picture, you might never guess that Anupama’s strong, unflinching gaze belongs to a victim of a devastating natural disaster. The truth is that the colourful clothing she wore was pretty much her only remaining possession.

I’m not sure how to describe something that takes place in a fleeting moment. Something can happen between two people in the fraction of a second a photograph is made. It’s not always present but I’ve experienced it often enough to recognise it when it appears. If forced to put it into words, I might say it’s a profound but intangible connection, an acknowledgement of the presence of trust.

I’m sure it’s conveyed in body language, in micro-expressions, probably. It cannot be faked or even anticipated. It’s the product of time spent paying attention to a person without a camera in the way. It is, I suppose, born of empathy, and without empathy it can never exist.

I made six frames of Anupama, lowered my camera a little, looked at her directly again. This was obviously not a time for laughter – context is key – she looked straight back, waiting.

I wanted to be sure that I had recorded the stoic expression in Anupama’s eyes. I was using a manual focus 21mm lens, much too wide for a close-up portrait. I didn’t want to change lenses and lose the moment. But I knew that trust, which I have clumsily failed to adequately describe, existed between us. I was able to step forward and make three more pictures at a proximity that would not have been possible without that undefinable … whatever it is.

The portrait below is full-frame, uncropped, made with a 21mm lens at a distance of, well, virtually zero.

We all carry an invisible personal space boundary, within which it feels uncomfortable for strangers to venture. I think pointing a camera at a person can risk puncturing that space, even from a distance, unless we have established some sort of rapport first.

I think it’s possible to step outside your own comfort zone and into a stranger’s, without either of you feeling compromised, if you’ve invested the time to build rapport.

Too often, I’ve seen people with cameras (let’s not call them photographers) treat strangers as little more than camera fodder. This is especially apparent in parts of Africa and Asia, where some visitors behave as if they’ve landed in a theme park, with local people reduced to colourful characters who exist solely to provide content for Instagram posts.

One of the worst examples of this regrettable behaviour can be witnessed each year at the Pushkar Camel Fair in northern India where, for reasons beyond my comprehension, hordes of camera-toting tourists buzz around like swarms of wasps, poking their lenses into the faces of camel-traders without so much as a nod of acknowledgement. Not everyone behaves this way, but even one would be too many. And there’s a lot more than one.

Anyway, I’ve ventured off-topic and also far beyond the limits of my clunky writing ability in an attempt to describe the indescribable. Perhaps you’ll get a sense of what I mean from Anupama’s beautiful, stoic expression.

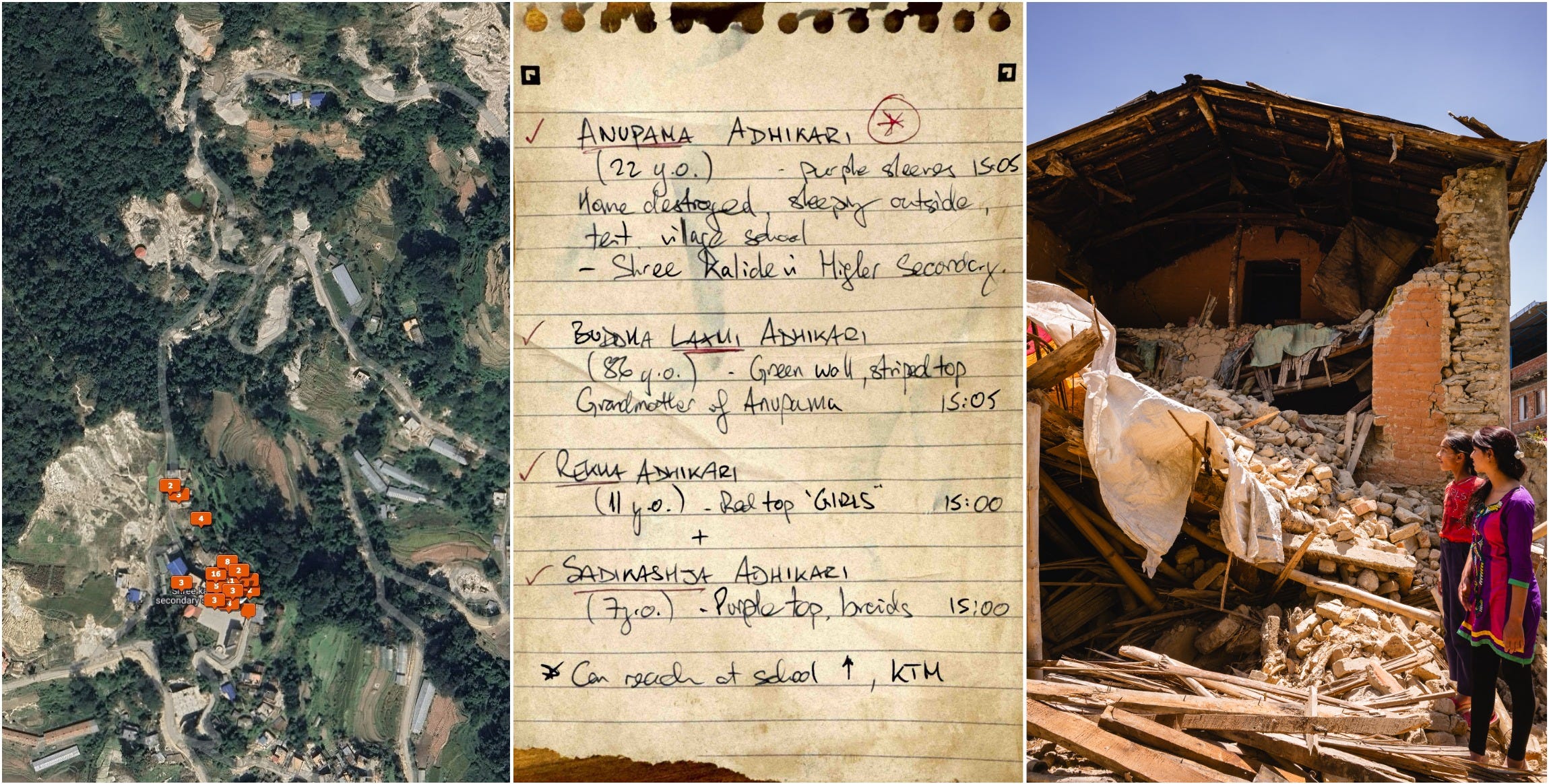

I’ve retrieved some of my notes from that day and placed them beside a Lightroom map showing where I made photos and a picture of Anupama and her cousin Rekha standing beside the rubble that was once their family home.

Also sleeping beneath a blanket in the school playground was Anupama’s 86-year-old grandmother, Laxmi.

Summary

If I had to choose, I’d say that making impromptu street portraits is my Happy Place. I love the sense of connection that they often produce. They are collaborative, as opposed to the more one-sided nature of candid photography, and they don’t require a big investment of time and money spent on portable lighting equipment.

They do, however, require our empathetic attention to a stranger and our willingness to say, without expectation of anything in return, “I see you.”

The good thing about writing far too many words about something which ought to be evident to some degree from the photos alone is that only readers with sufficient attention spans will have reached this point. So to you, dear reader, congratulations. You definitely possess the unhurried patience necessary to make engaging street portraits.

By way of reward, here’s one of my favourite street portraits. A man dressed, inexplicably, in a Chinese New Year costume on a back street in Bangkok’s Flower Market. When I met him, Chinese New Year was six months away.

Survey

My editor tells me repeatedly that I must make these newsletters much shorter. I promised to include a poll and will stand by the results. Please do me a favour and click to answer the survey question.

Would you prefer it if Beyond the Frame newsletters were shorter?

Statistically, 35 readers will be celebrating their birthday today. To you, I send birthday greetings. I can confirm that the 30th of June is the very best day of the year for a birthday. 😬

In the next edition I’ll share the promised guide for backing up image files without a computer.

I leave you with a final, gleeful portrait from Nepal.

Until next time, go well.

Oh…I forgot to say…long form is a good thing. Too much of our time is taken up by short grabs of information and quickly moving on to something else. This doesn’t allow time for ideas to resonate and percolate but your writing style does that.

Another insightful newsletter. I’ve voted no to shorter….I love the level of detail. The newsletters are not just the how to take photos but, as evidenced by this one, you give valuable insights into the why. Making photos that give you and others connections and memories is extraordinary and something tangible you can see in them. I appreciate the advice and going forward will take making connections as my goal. Thanks for the inspiration.