Beyond the Frame 44/

AI Quiz, how well did you do? The Remains of Elmet by Ted Hughes and Fay Godwin. Quantum Entanglement photos.

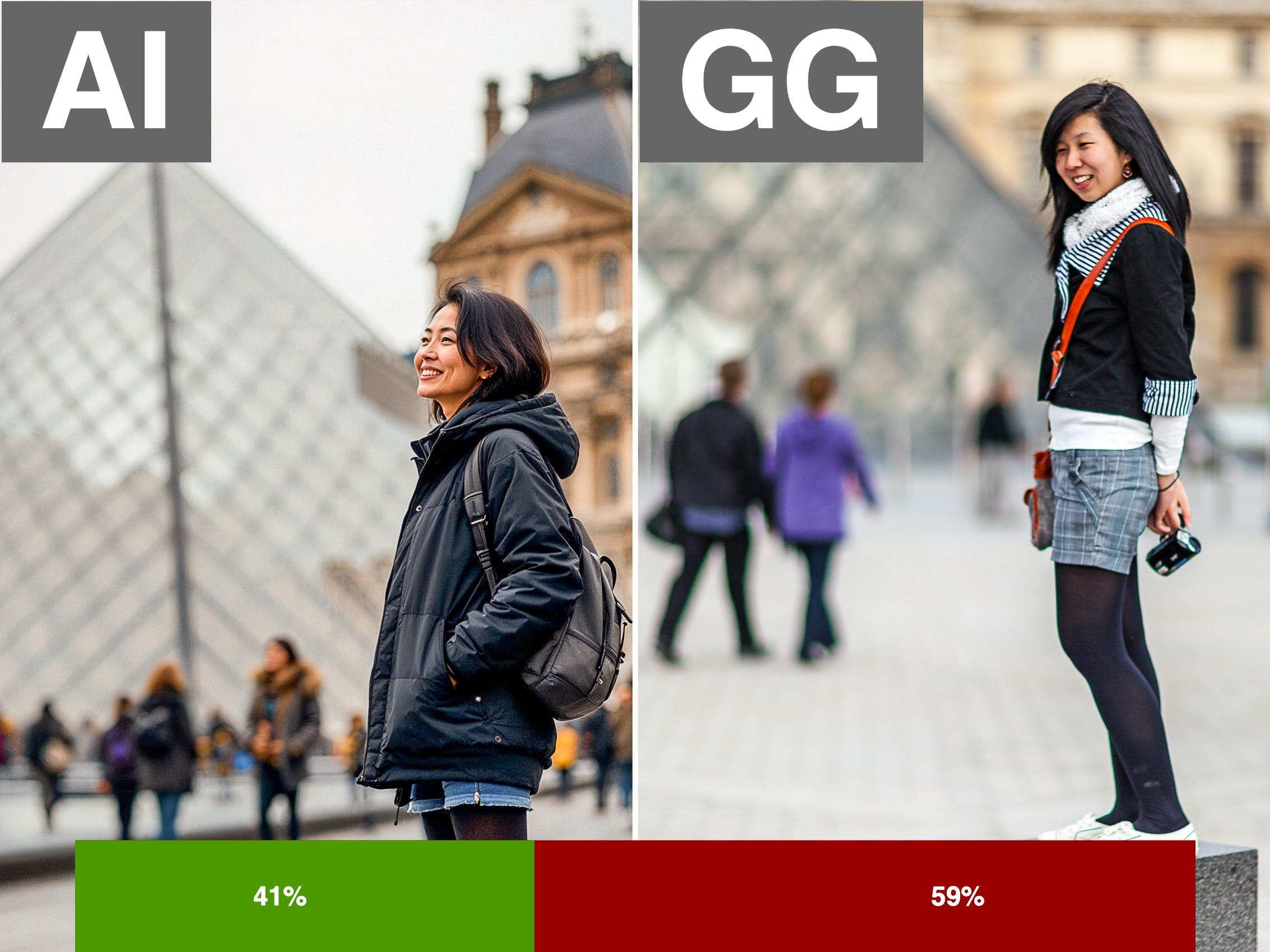

AI Quiz Results

Thank you to the hundreds of you who took the AI quiz in my previous newsletter.

There’s good news and bad news.

The good news is that the Substack poll recorded all your votes successfully and calculated an accurate percentage.

Ahem! That sound you can hear is the bottom of a barrel being scraped.

The bad news is that most readers were not able to correctly identify the AI-generated images. 😕

The AI images are on the left, my photos are on the right. (If you saw a tick when you made your selection, that’s just Substack’s notification that your vote was recorded, not an indication that you were correct.)

Remember, the challenge was to choose the image that you thought was AI-generated. Let’s see how you voted:

I suspect some readers might have been misled by the slightly awkward hands in the real-life subject on the right. AI has used to have a reputation for not being able to generate hands and fingers convincingly. The AI model on the left, perhaps knowing this, cunningly hid her hands in her jacket pockets. Sorry.

Perhaps the man’s make-up in the real photo is just too perfect? He’d take that as a compliment, I’m sure. The implication that the AI man’s make-up and complexion is more “natural” is perhaps an indication of how convincing AI-generated images have become.

I am relieved that a majority of readers were able to correctly identify at least one of the AI-generated images, although it’s small consolation.

Perhaps it won’t come as news to many people but it seems that we aren’t able to confidently distinguish between real photos and AI-generated images.

Does it matter?

It’s always been possible to manipulate photographs. Isn’t this just a more sophisticated and more accessible means of doing so?

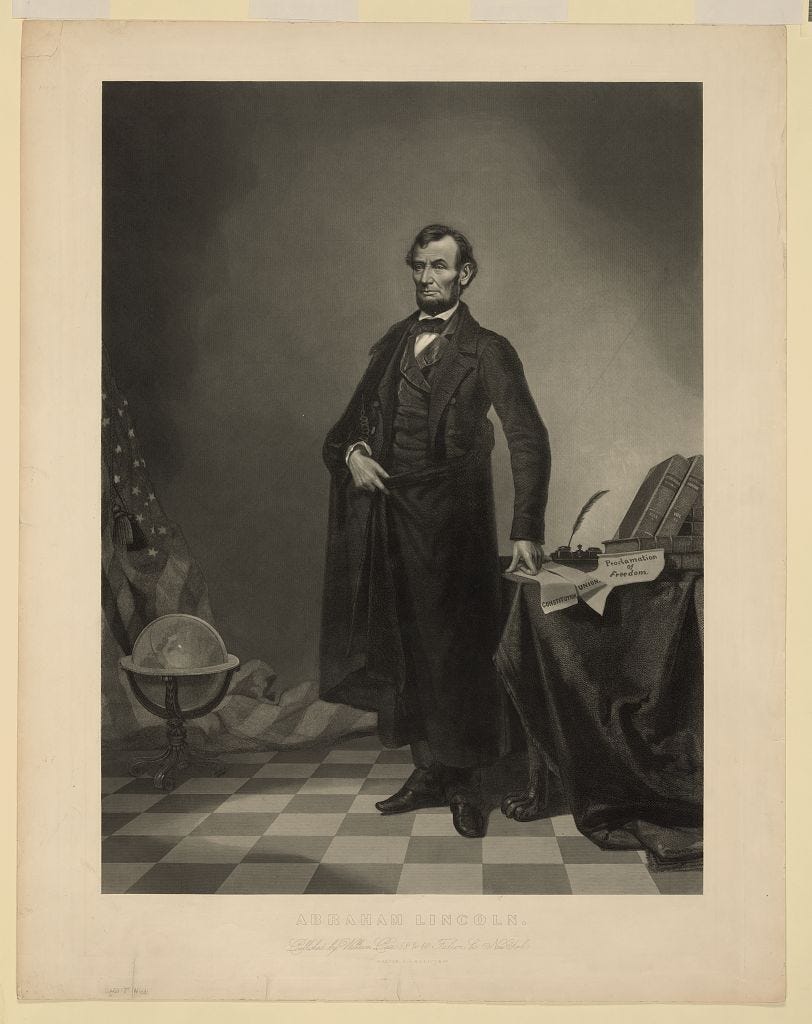

Many portraits of Abraham Lincoln were carefully stage-managed. After Lincoln’s assassination, in order to make him appear more statesmanlike, “Thomas Hicks superimposed Lincoln’s head onto the body of John C. Calhoun—the virulent racist and slavery proponent who did not exactly see eye-to-eye with the 16th president.” (Atlas Obscura)

After Nikolai Yezhov’s execution in 1940, he (not so) mysteriously disappeared from official photographs of Stalin. Leon Trotsky suffered a similar fate. Well, they both ultimately suffered much worse fates than being airbrushed out of photos but, photographically speaking, they “disappeared”.

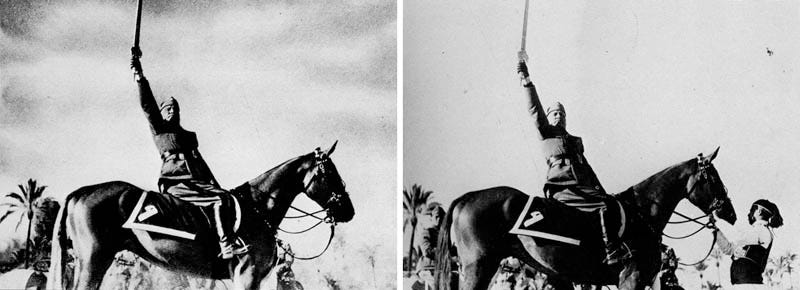

Benito Mussolini thought he’d look more heroic if it appeared that he could control a horse through the power of his mind and famously powerful knees, rather than requiring a helpful handler.

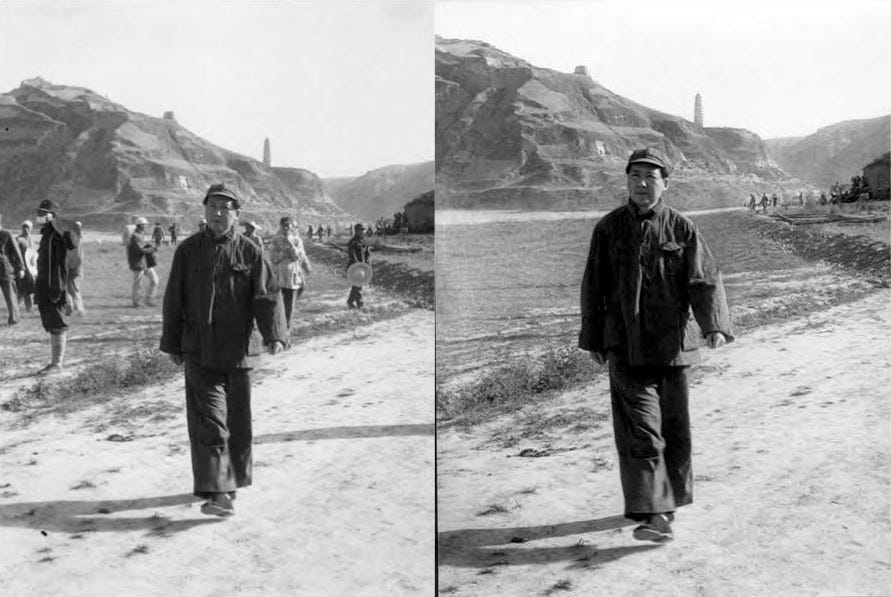

Photographs of Mao Zedong were routinely manipulated; the Chairman preferring to be pictured in heroic isolation.

Whilst it’s not a new phenomenon, image manipulation historically required at least a modicum of skill and some evidence of the changes would be apparent to anybody who looked closely. These things are no longer true. Now we can all make significant changes to an image in a matter of seconds. AI can generate an entirely new image, requiring only a simple spoken or typed prompt. No skill is required. No clues remain.

There’s nothing new about bullshit. Other technological advances—the printing press, television, the internet—have all increased the speed and volume with which it can be spread. Is AI any different? Are we about to be buried beneath an avalanche of bullshit from which no amount of digging will free us?

You’ll like this: in an irony-rich moment I asked Chat-GPT to suggest what the consequences might be if humans cannot differentiate between authentic and AI-generated images.

I’ll paraphrase the AI response:

Erosion of trust and increase of misinformation. Fabrication of events, distortion of truth, reputational damage, identity theft, zero credibility of documentary evidence (photojournalism), fraud, deepfakes, personal memories may diminish, reality distortion…

And, my personal favourite:

“If AI can generate perfect images instantly, human-created photography might be undervalued, affecting the industry and livelihoods of photographers.” (Chat-GPT)

Cheers!

There are some steps being taken to try and mitigate the risks, although I fear the political will to address AI-related issues might always lag several steps behind the technological advancements.

AI Legislation

In the United States, some AI companies have made a voluntary pledge to identify AI-generated images with a watermark. In Europe, the Artificial Intelligence Act is designed to provide protections.

So that’s alright then.

Summary?

When I began writing about AI last week, I did so with an open mind. I expected to write about the pros and cons, planned to show some examples to illustrate how far AI has advanced and balance that with some suggestions for how AI might improve our lives. I had the whole “it’s amazing for medical diagnoses” argument waiting in the wings. But the more I have researched and the more I have learned, the more despondent I have become.

Perhaps I’m simply too old to fully appreciate the benefits and younger generations will embrace AI, finding a way to employ it as a productive tool that enriches their lives.

Who am I kidding? We’re all going to die!

(My editor suggests I should point out that the last sentence is hyperbole added for humour. It isn’t. We are.)

I have enough material to write 15 more newsletters on the subject but I don’t want to think about Artificial Intelligence any more. It’s creepy and I don’t trust it.

And so, probably to your relief as much as my own, I have retreated to the reassuring familiarity of some proper, old-school photography, which I hope will soothe your soul as much as it has mine.

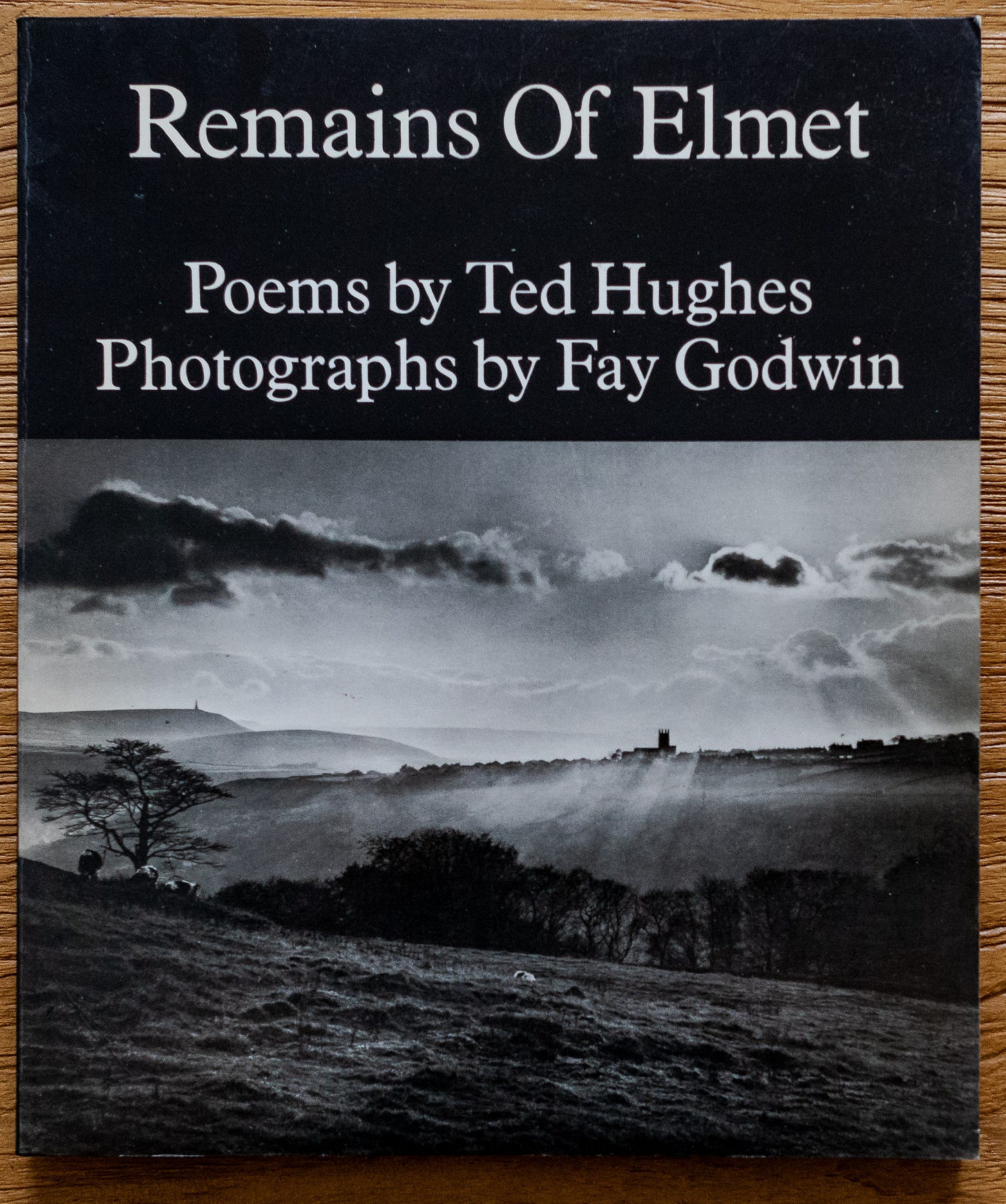

Remains of Elmet

I sought much-needed solace after thinking too much about Artificial Intelligence. I made a pot of Lapsang tea, dropped the needle on Roddy Frame’s Western Skies and pulled Remains of Elmet from my bookshelves.

In their collaboration, Ted Hughes wrote poems to accompany Fay Godwin’s photographs.

Elmet was an independent, Celtic kingdom in the 4th–7th centuries in what is now northern England, roughly where we now find West Yorkshire.

“The Calder valley, west of Halifax, was the last ditch of Elmet, the last British Celtic kingdom to fall to the Angles. For centuries it was considered a more or less uninhabitable wilderness, a notorious refuge for criminals, a hide-out for refugees. Then in the early 1800s it became the cradle for the Industrial Revolution in textiles, and the upper Calder became ‘the hardest-worked river in England’

Throughout my lifetime, since 1930, I have watched the mills of the region and their attendant chapels die. Within the last fifteen years the end has come.

They are now virtually dead, and the population of the valley and the hillsides, so rooted for so long, is changing rapidly.” — Ted Hughes from the introduction to Remains of Elmet

“A wind-parched ache”

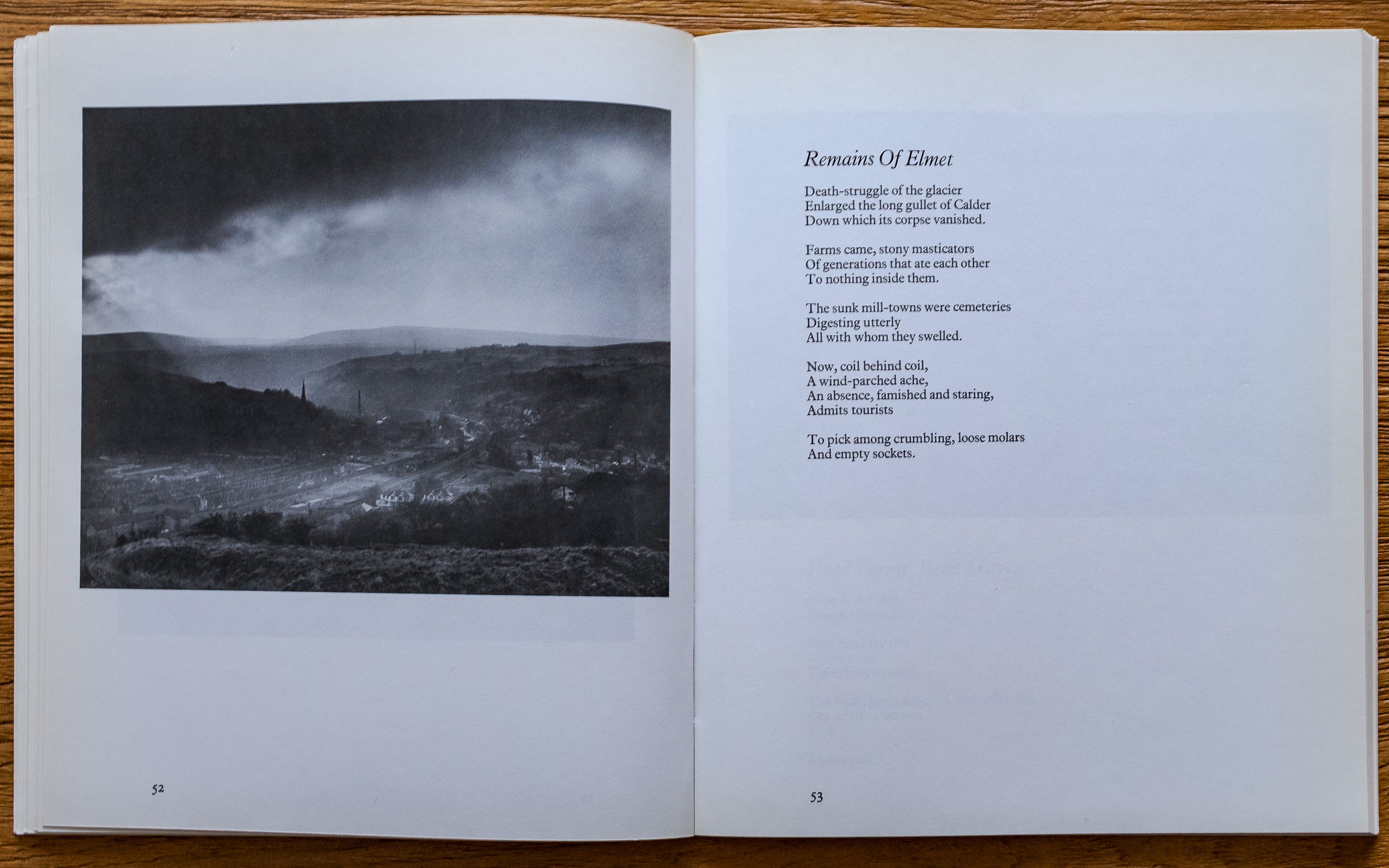

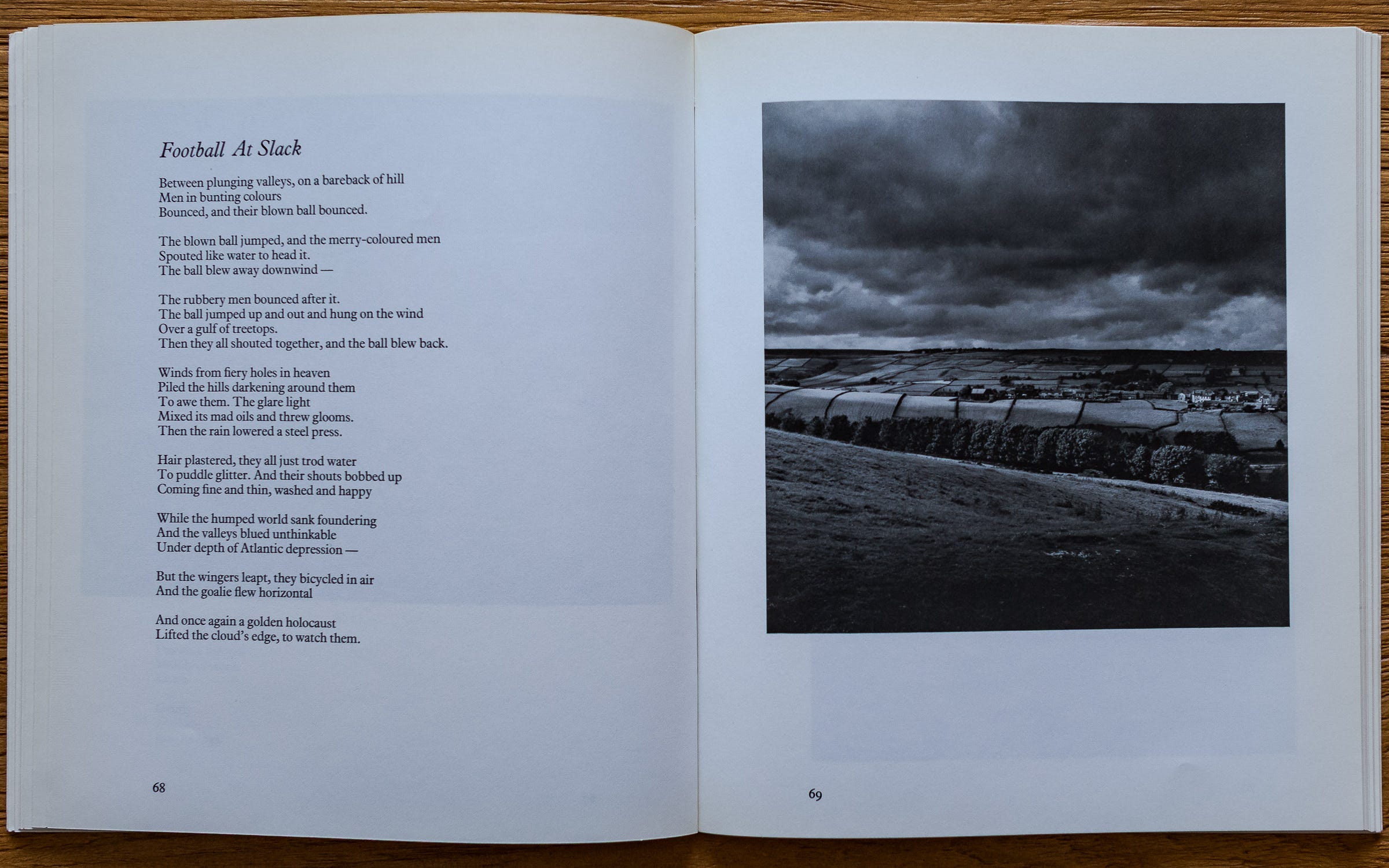

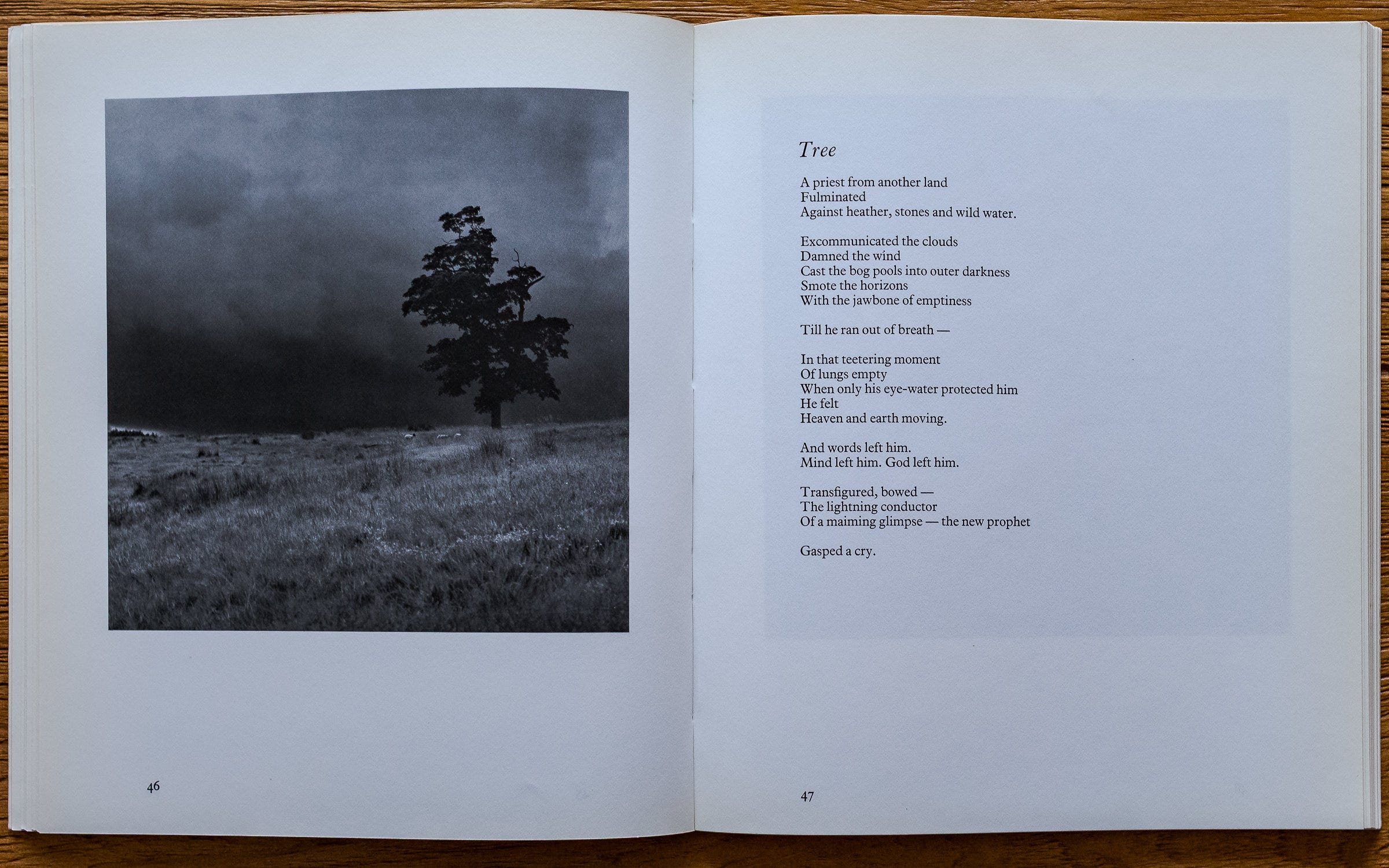

At first glance, Fay Godwin’s photographs might appear, like the region, bleak and sombre. But amidst the dark clouds, lonely trees, and abandoned buildings, there is always the promise of light.

Godwin’s photograph of the Calder Valley is twinned with Hughes’s poem, Remains of Elmet. Both the picture and poem depict a landscape altered by time. Beneath a dark grey cloud we see hints of industrial chimneys and thin slivers of light reflected in sections of the Calder river. Hughes laments the remains with a characteristic economy of perfectly-chosen words.

There’s a beautiful simplicity to Remains of Elmet. Godwin makes a photo of a rock, Hughes writes a dozen lines about it. Yet both picture and poem are carefully considered, thoughtful, the result of hours of contemplation, no doubt.

The collaboration is an elegy for a part of the world that both Godwin and Hughes clearly held in great affection. They reflect upon the vestiges of an industrial past, where nature is reclaiming a landscape that humans briefly shaped.

Both poems and photographs are occasionally jagged and minimalist, much like the features of Elmet’s landscape. Importantly, for this reader, it is a truly human work of art. I think of Fay Godwin, traipsing over the moors and through snow drifts, silently composing her photographs and then I imagine Ted Hughes, looking at Godwin’s black and white print, perhaps in a quiet corner of his local pub, turning his eyes upward in contemplation, pen poised…

I know we need art. I hope we need artists.

Remains of Elmet is long out of print and can be hard to find. I discovered a 1979 edition on the World of Books website, where one can often find second-hand copies of rare books. At the time of writing, there’s one copy available on Amazon.co.uk.

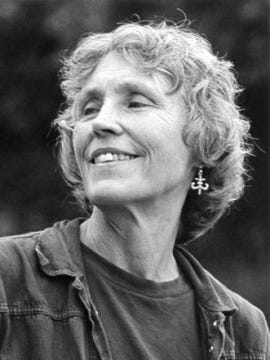

Fay Godwin

I mentioned Fay Godwin’s appearance on the BBC’s long-running radio series, Desert Island Discs in Beyond the Frame 27/.

Quantum Entanglement

And finally, speaking of collaborations, for the past 18 months my friend Debbie and I have each made a photo every day.

Debbie and I live in different countries, we don’t have a theme for our photos, don’t discuss in advance. We each make a photo and combine them in a diptych, inviting serendipity to contribute. Usually, Debbie is in London and often shares photos from her daily commute. This month she’s in New Zealand and has swapped grey skies for blue.

Here are some recent results.

I began my part-time Arts course today. I have a reading list as long as both arms, a seemingly never-ending list of usernames and passwords and have already been presented with some “Creative Challenges” to be completed in the next two weeks. Perhaps that AI thing might come in useful after all. 😬

Until next time, go well.

Beyond the Frame is a reader-supported publication. The newsletter is a labour of love that only exists thanks to the patronage of readers. Please consider joining the community of supporters. Your support makes all the difference.

The Directory contains a full list of newsletters, tagged and searchable by content.

The Resources page contains links to recommended photographic resources, including books, camera gear, accessories, software, contests, grants, and online tools.

Loved this post.