Beyond the Frame 39/

Looking at the life and work of Sergio Larrain and enjoying a romantic flight of fancy with Geoff Dyer and Robert Capa — with an invitation for readers to get creative.

Manics

Before I kick off, the Manic Street Preachers released their 15th studio album today, which is a reason to be cheerful. I’ve played it on repeat whilst writing this edition and so it inevitably infuses what follows. It’s not an obvious choice to accompany a reflection on the work of Sergio Larrain or for reading a romantic interpretation of a Robert Capa photograph but, nevertheless, should you be tempted to begin playing the album as you read, I think you would be a winner.

Valparaíso — Sergio Larrain

“A sordid yet romantic city.”

The Magnum Gallery in Paris recently hosted an exhibition of Sergio Larrain’s photographs from Valparaíso in Chile, which I mentioned in Beyond the Frame 29/.

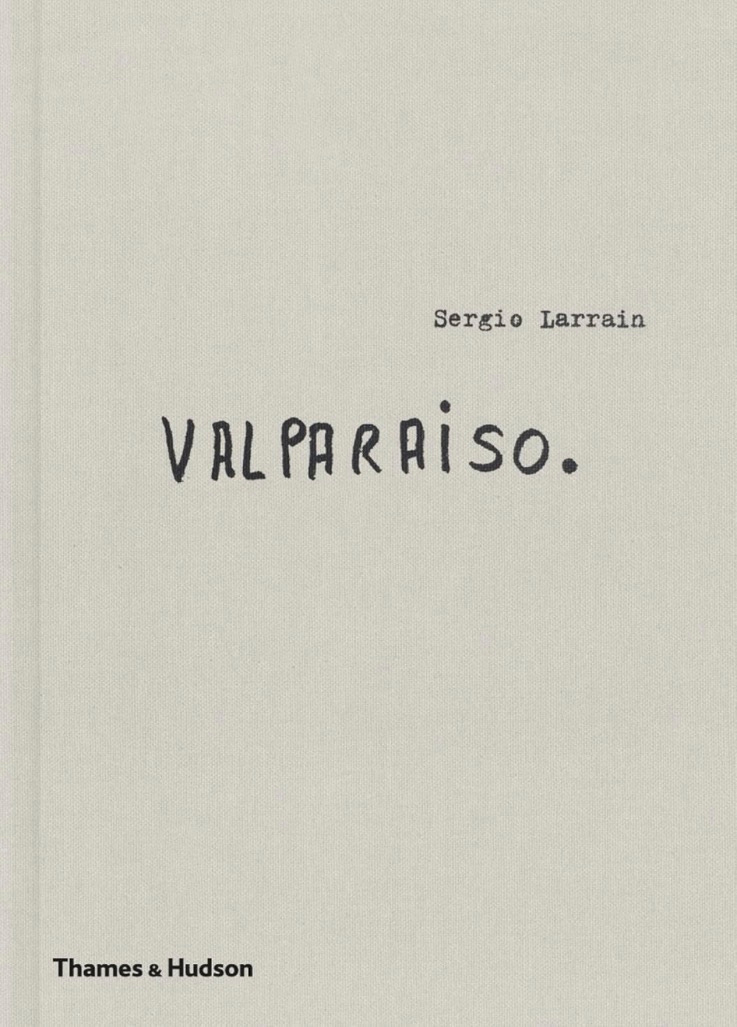

Exciting news for photography lovers: A new collection of Larrain’s Valparaíso pictures was published this week.

Who was Sergio Larrain?

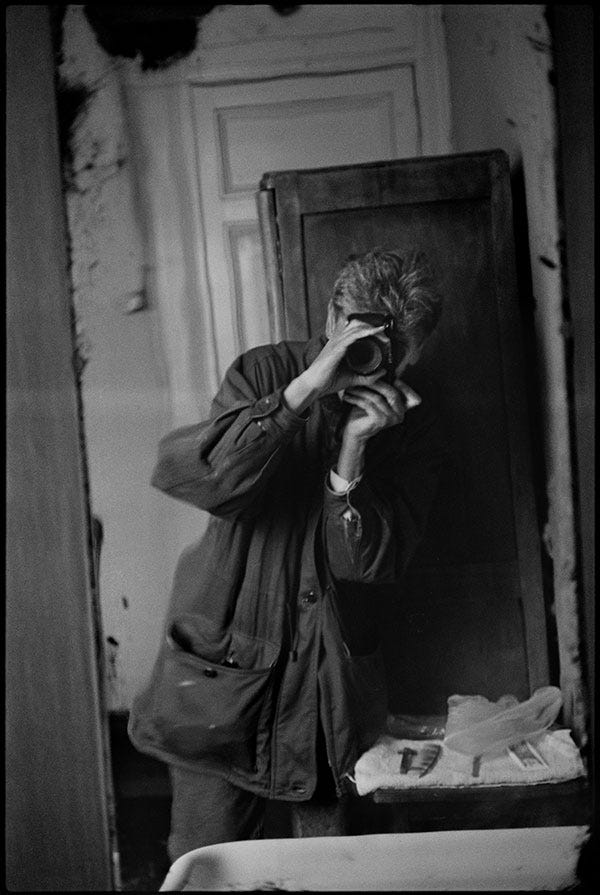

Sergio Larrain was born into a wealthy Chilean family but apparently struggled with his father’s overbearing personality. “Sergio hated his father”, his younger sister said. Sergio found solace in photography and moved to Europe in the 1950s, where he found some commercial success but, alas, little in the way of contentment.

Artist Sheila Hicks worked with Larrain in 1957, “He would play with the camera. He was light on his feet, bouncing around, dancing. He was very clever about insinuating himself into spaces. He was like a butterfly.”

Descriptions of Larrain’s working style remind me of grainy footage of Henri Cartier-Bresson at work. He also danced on tiptoes with a camera in his hand and possessed the grace of a ballet dancer.

Cartier-Bresson and Larrain met in Paris in 1959. Henri personally invited Sergio to join the Magnum agency but less than a decade later Larrain had seemingly abandoned photography and was living a hermit’s life in Chile.

Thirty years after Sergio’s withdrawal from public life, Agnès Sire, a young Magnum picture researcher, found one of Larrain’s pictures in the agency’s archives. She tracked Larrain down through an old PO Box address and gently convinced him to allow his work to be published.

Reports claim that Larrain became increasingly eccentric in later years. He wrote about walking through Valparaíso in a state of meditative calm and about his pursuit of “satori”, a Zen Buddhist term for a kind of intuitive, unfiltered experience of reality, beyond intellectual or rational understanding.

“He railed against the destruction of the planet through pollution, overpopulation, the ‘parasites’ who live off other people’s taxes and the ‘predators’ of big business. ‘We are going towards a garbage deposit turning around the sun inhabited by millions of people attacking and robbing each other permanently, forever.’”

I don’t think any of that sounds remotely eccentric. But perhaps that says as much about me as it says about Larrain. I’d bet that most people reading this would agree that more ‘satori’ and fewer ‘predatory parasites’ in the world would be a very welcome development. Now more than ever!

This might be an appropriate point to remind readers that support for organisations which help to protect and sustain independent journalists is growing ever-more important with each passing day. I wrote about this recently in Beyond the Frame 36/.

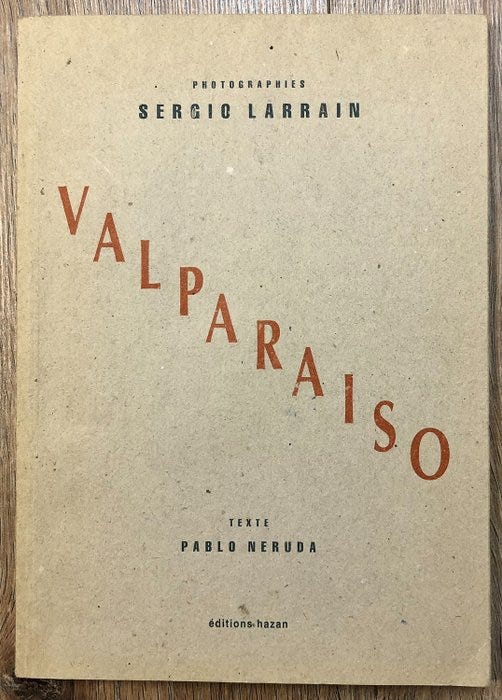

The original French language 1991 Edition

The first collection of Larrain’s Valparaíso photographs was published in 1991.

“Valparaíso quickly became one of the most collectable and influential photo books. It did not so much document the place as the feeling of moving through it and glimpsing it in passing: its stray animals, poor children, loitering men, sailors and prostitutes. The book’s reputation was fed by myth as well as mastery. Larraín had long since disappeared. It seemed like the work of a ghost.” — Simon Willis for the Financial Times

After publication of the original book, Larrain revealed that he had continued to photograph Valparaíso in the intervening years. The new edition significantly expands upon the original and contains many of Larrain’s later photographs..

The 2025 English Language Edition

“Sergio Larrain’s Valparaíso is based on a layout designed by Larrain in 1993 in response to the original French edition of 1991. It features a text by Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda, specially written for Larrain; an essay by Agnès Sire; and a selection of previously unpublished photographs taken between 1952 and 1992, expanding the original thirty-six images to a total of 120. Handwritten notes and texts by Larrain himself accompany the photographs.” — from the publisher’s notes.

Read on to learn how you could win a copy of the new edition of Sergio Larrain’s Valparaíso.

Further reading

You can find more of Sergio Larrain’s photographs from Valparaíso on the Magnum website.

You can also read more about Sergio Larrain in this excellent Financial Times article, some of which I have paraphrased here.

Geoff Dyer and Robert Capa

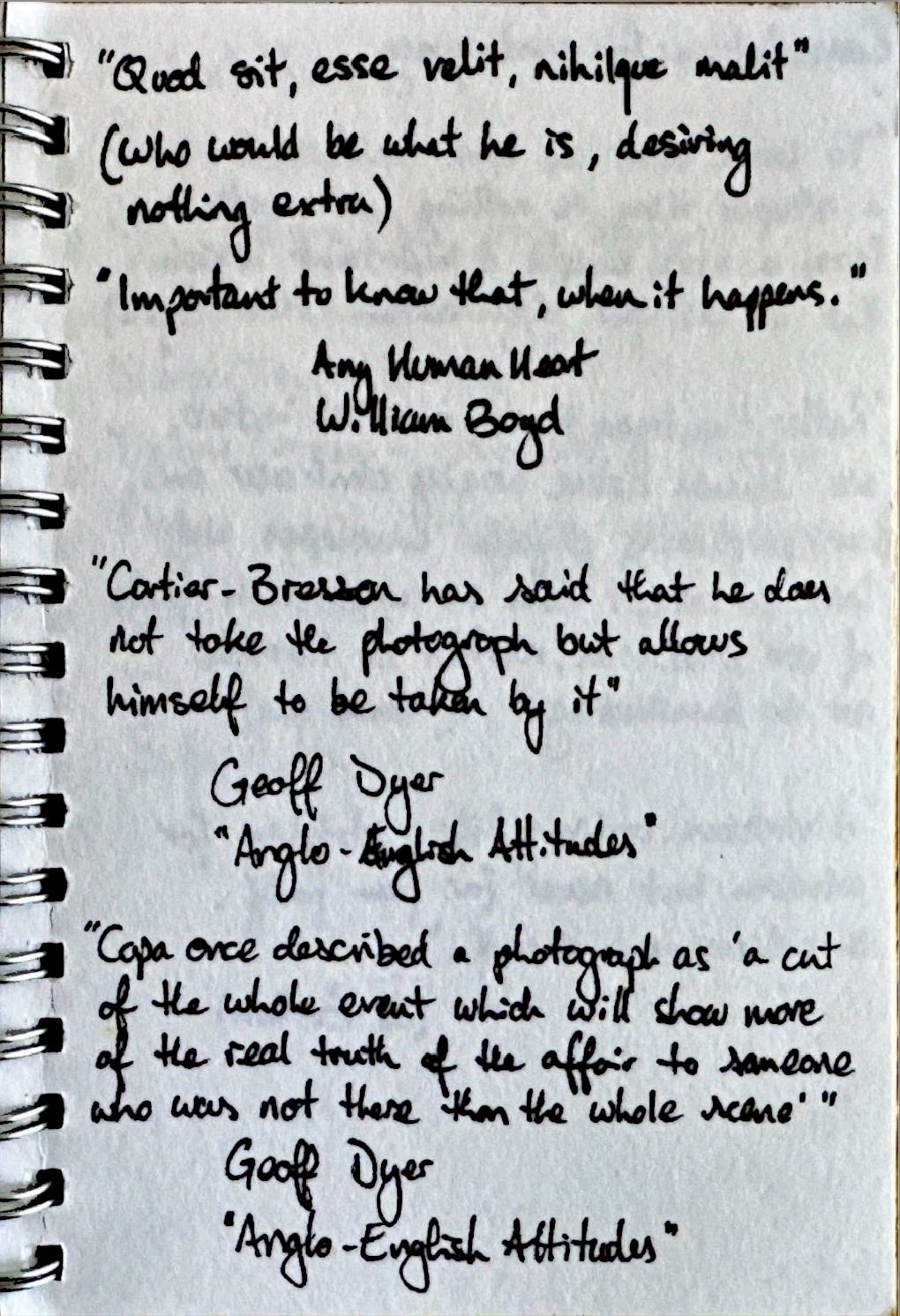

22 years ago, sitting inside a rain-soaked camper van in the remote reaches of New Zealand (my editor tells me I should not say “arse-end of New Zealand” — but it was), I copied a couple of sentences from Geoff Dyer’s book, Anglo-English Attitudes: Essays, Reviews, Misadventures.

“[Robert] Capa once described a photograph as ‘a cut of the whole event which will show more of the real truth of the affair to someone who was not there than the whole scene’.”

I’ve often thought about that quote, especially when working on assignment. Asking, “what is the essence of this place / this event / this scene?” can help focus attention on the critical “cut of the whole event”that will convey the “real truth of the affair”.

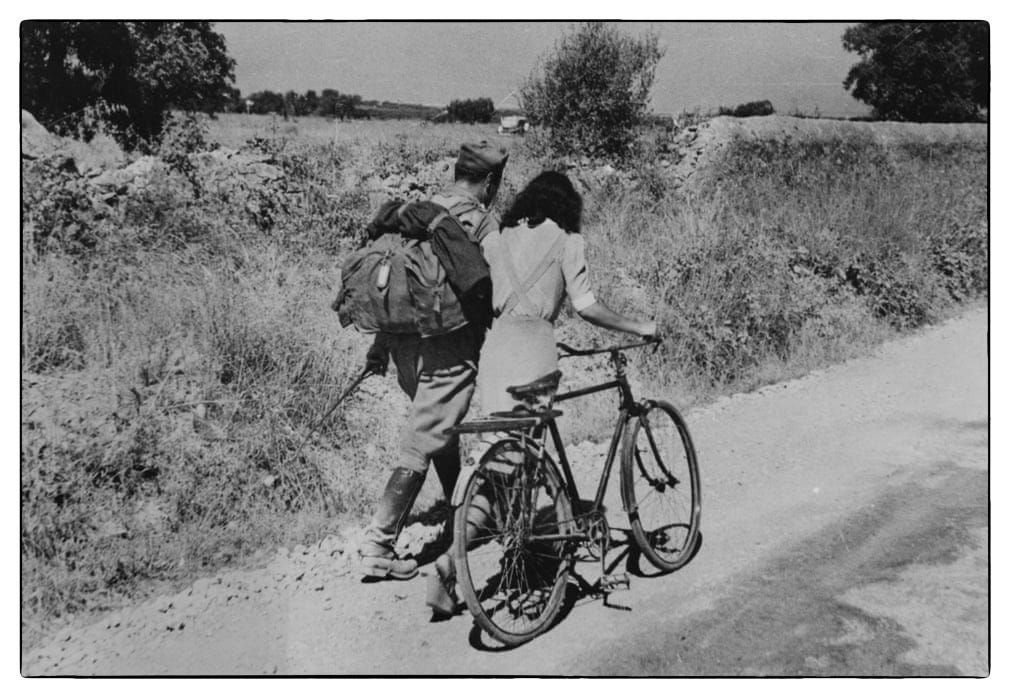

In a chapter that I often return to, Geoff Dyer goes on to look at one of Capa’s photographs taken at the end of the Second World War.

“Works of art urge us to respond in kind and so, looking at this photograph, my reaction expresses itself as a vow: I will never love another photograph more.”

— Geoff Dyer. Anglo-English Attitudes.

“I will never love another photograph more” is, surely, the pinnacle of devotion. I’m not confident that I could elevate my loyalty to a single image to such lofty heights.

Dyer discovers different captions for Capa’s photograph. On the back of a postcard one caption reads, ‘Italian soldier after end of fighting, Sicily 1943.’ Later, in a book of Capa’s work, the accompanying caption reads, ‘Near Nicosia, Sicily July 28, 1943. An Italian soldier straggling behind a column of his captured comrades as they march off to a POW camp’.

(Interestingly — or perhaps confusingly — whilst researching this photograph, I found it in a Guardian article with a caption, ‘Lovers’ Parting near Nicosia, Sicily’, which provides yet another, quite different interpretation.)

The two (three) captions seem contradictory but Dyer concludes that both are misleading, not least because neither mention the woman in the picture.

“The visual truth of the photo pushes the circumstances in which it was taken beyond the edge of the frame.”

In a section that’s typical of Geoff Dyer’s writing, he veers into unpredictable territory, decides to dismiss both captions and, instead, to “transcribe the caption inscribed within [the picture].”

Dyer lists the things he sees in Capa’s photograph, things that only a devotee who has vowed never to love another photograph more might have the level of attention necessary to discern.

“The hot Mediterranean landscape. Dust on the bicycle tyres. The sun on her tanned arms. Their shadows mingling. The flutter of butterflies above the tangled hedgerow. The crumbling wall at the field’s edge.”

In Dyer’s devoted hands, Capa’s photograph begins to shimmer.

If we can muster the necessary levels of patience and attention, we might, like Dyer, begin to hear, “the rustle of cicadas, the noise of his boots on the road, the slow whirr of the bicycle.”

Exploring a photograph with this level of attention can fill us with longing too. We yearn to know more.

“When did they meet? Have they made love? How long have they been walking? Where are they heading? How long is the journey?”

In a section that still gives me goosebumps when I read it (and I read it often), Dyer rewrites the official captions with a lyrical description that, for me, rewards the attention given with abundance.

“They do not care how long the walk ahead of them is; the greater the distance, the longer they can be together like this. She will ask about the things that have happened to him; he will be hesitant at first, but there is no hurry. She begins to remember his silence, the way it was implied by his handwriting, by the letters he sent.

They will walk along, their shoulders bumping, noticing everything about each other again, each a little apprehensive of disappointing the other in some small way.

At some stage, perhaps when they are resting by the roadside or perhaps when they lie down to sleep under the star-clogged sky, she will turn to him and say, ‘Am I still as pretty as when you left?’ Knowing what his answer will be, feeling the roughness of his hand as he pushes the hair behind her ear, watching his mouth as he says, ‘More. Much more.’”

An invitation

I appreciate that it’s a romantic flight of fancy and there are often times when photographs and captions must adhere to strict journalistic principles. But, really, we should occasionally look at a photograph and allow our imaginations to see the flutter of butterflies above the tangled hedgerow and hear the slow whirr of the bicycle.

With that in mind, here’s an invitation:

Your devotion to a photograph doesn’t have to be as absolute as Geoff Dyer’s. If you find a picture that speaks to you, I invite you to write a short, alternative description for it.

It can be romantic or not, lyrical or understated, based in fact or entirely fictional. My invitation is for you to invest a photograph with a level of attention that might feel uncomfortable at first. It is a symptom of the age, regrettably, that we have become accustomed to glancing at images for only the most fleeting of moments.

I suspect — indeed, I know — that our attention is invariably rewarded and if we give our imaginations permission to fly freely, our muse might descend and offer us glimpses of what’s happening beyond the frame.

(See what I did there?)

As an added incentive, I’ll send a copy of Sergio Larrain’s Valparaíso to the person who sends me the image and description that resonates most.

The photograph doesn’t need to be your own — in fact, it’s probably best if it’s not one of your photos as you’ll be familiar with the context and that might limit your potential for imaginative flights of fancy.

Find a photo that fascinates you. Give it your full attention. When your attentiveness begins to breathe life into the image, write down what you see, hear, taste and feel.

You can send your description and photo by email or use my website contact form, including a link to the picture.

There’s also still time to submit your entry to win your choice of books from my list of Most-Loved Books of 2024.

I hope that presses your creative buttons. Enjoy and good luck.

The Directory contains a full list of newsletters, tagged and searchable by content.

The Resources page contains links to recommended photographic resources, including books, camera gear, accessories, software, contests, grants, and online tools.

Beyond the Frame is a reader-supported publication. The newsletter is a labour of love that only exists thanks to the patronage of readers. Please consider joining the community of supporters. Your support makes all the difference.

What a wonderfully gut-wrenching episode. Apart from being exposed for the first time to the Manic Street Preachers, of whom I'd never heard (new record blaring in the background), the ruminations around the Capa photo were very moving, even disconcerting. I hope to find a few moments to accept the invitation. Brilliant stuff, Gavin, thank you...

Thought provoking as always. Thank you for bringing Geoff Dyer back onto my radar. And for the challenge, not just yours now but to take the time to delve into images rather than view and move on.