Beyond the Frame 28/

“Make more photos of fewer things.” A reminder that photography should be dynamic; a ballet of observation, movement and timing.

“Make more photos of fewer things.”

This is a phrase shared with students at the Bangkok Photo School. We printed it in a bold typeface at the top of Cue Cards handed out in class.

Chinese Opera

It’s become my mantra, a reminder to “work the scene” and to “keep photographing, even after the magic has gone”.

I don’t recall where I first learned these phrases. I wrote them in the margins of The Passionate Photographer, a book by Steve Simon, which might be the most heavily annotated book in my library. Many highlighted sections are accompanied by my handwritten exclamations of agreement, “This!” “YES!”

It’s not a complicated or challenging suggestion. Spend more time photographing fewer things. Yet we tend to do the opposite when we start out. We frame, adjust exposure, make a photo, maybe two, we’re done. What’s next? It requires conscious effort to remain, to keep the camera ready, patiently noticing subtle changes in the action, learning to anticipate gestures and subtle shifts in the light.

Backstage at a travelling Chinese Opera, performers spend a long time applying their traditional make-up. The only light is from naked bulbs, harsh at the source, rapidly fading into darkness.

It’s the perfect place to practice the art of “working the scene”. It’s relatively tranquil before the curtain rises. Each performer is applying their own make-up, peering intently into a well-travelled mirror, positioning lights to illuminate their faces.

I don’t know the precise ratio but I’d guess that I usually make one usable image for every 15–20 clicks of the shutter. It might be a lot lower than that, especially now that I don’t have to load a new film after 36 exposures. And that’s fine by me. I know I’m in good company.

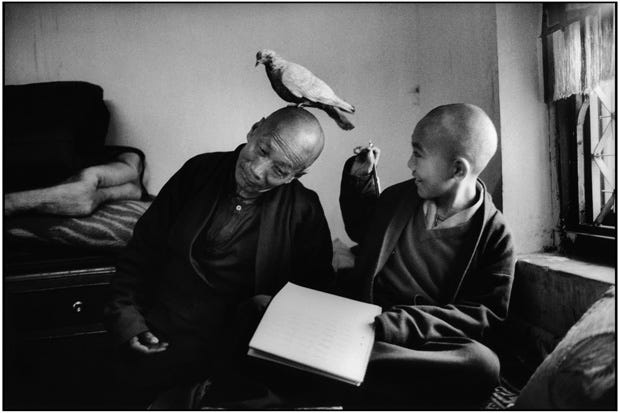

Buddhist Monks — Martine Franck

In an interview with the Guardian (which I’m alarmed to see I bookmarked nearly 18 years ago), Martine Franck said, “I don’t look at my photographs very often, but this picture always makes me happy. It was just such a perfect moment.”

“I was there for an hour, just sitting quietly in a corner, observing. I never imagined for a second that the bird would perch on the monk’s head. That’s the wonder of photography - you try and capture the surprises.

I was in the right place at the right time, with the right lens on. If I’d had a zoom lens on, I wouldn’t have had time to set it at the correct distance. In fact, I had two Leicas, a 35mm and a 50mm, both already adjusted for the light, and the 35mm did the job.”

Preparation

Patience

Prime Lenses

I think we might have accidentally stumbled upon the brilliant simplicity of good photography.

P.P.P.

You’re welcome 😬

Contact Sheets

I found Martine Franck’s contact sheets in Magnum’s unimaginatively titled but otherwise magnificent book, “Contact Sheets”.

You’ll notice that the selected image is the 7th frame in the sequence she made, and there are seven more frames after that. 14 frames when the pigeon is sitting on the tutor’s head. Some of us might have been tempted to take two or three frames and assume we’d caught the moment.

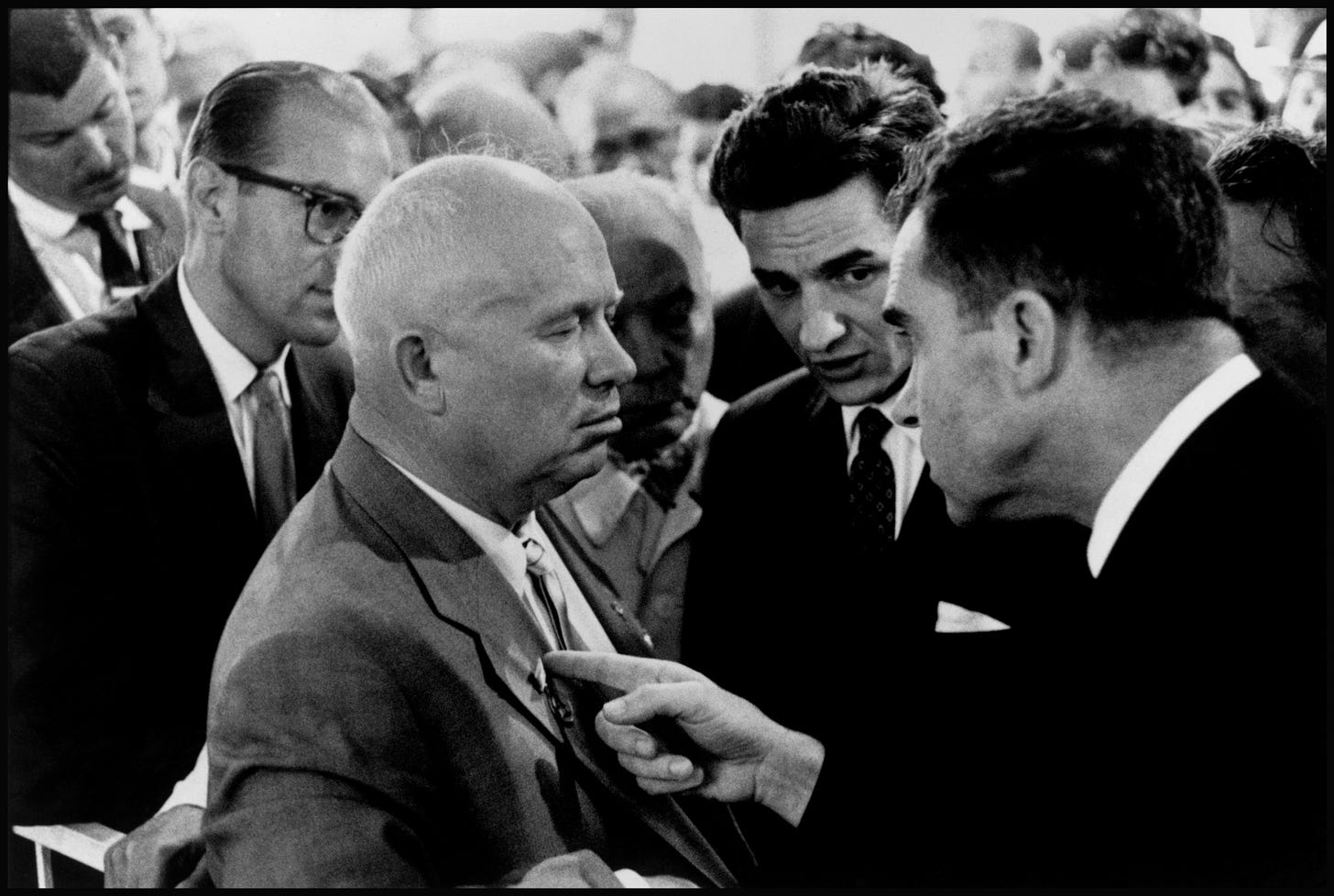

Kitchen Debate — Elliott Erwitt

Here’s another example. In 1959 Elliott Erwitt photographed an exchange between US Vice-President Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev (Erwitt wasn’t actually part of the Press Corps, he was photographing refrigerators for a commercial client at an exhibition of consumer goods).

The picture came to symbolise “the American people standing up to the Soviets”.

The way Erwitt’s contact sheets are arranged in Magnum’s book is misleading. The selected frame was actually near the end of the sequence, not the first. By my calculation, Erwitt had made at least 45 frames before Nixon’s finger-jabbing gesture.

Now, sure, if two world leaders are standing right in front of us, we might all keep pressing the shutter, hoping not to miss a crucial moment. But there’s no reason that same logic shouldn’t be applied to any other situation.

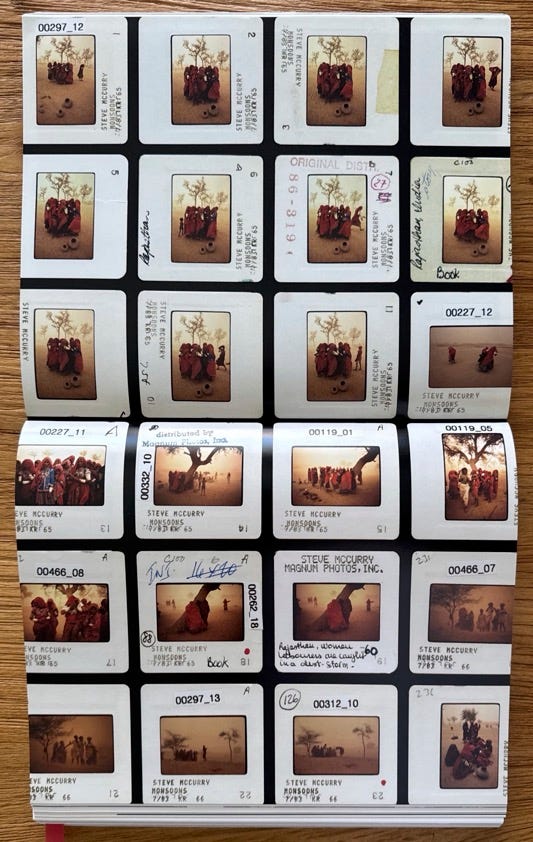

Dust Storm — Steve McCurry

I’d be willing to bet a pound to a penny that Steve McCurry got through at least one roll of Kodachrome making this image of women sheltering from a dust storm.

Magnum’s Contact Sheet book shows us 24 of McCurry’s slides. The first 11 show very slight variations in framing. In some, one woman is standing slightly apart from the group. Would those versions be as iconic as the versions with the women huddled together in a group? I’d say, not quite.

Summary

What’s the point of all this? It isn’t my suggestion that throwing a lot of mud at the wall improves our chances of something sticking. Well, that might be mathematically true but it really isn’t the point I’m making.

It takes a few frames to get into the groove, a few frames to synchronise with the action, to feel the rhythm of the scene.

I’m struggling to find a sporting analogy… a golfer taking practice swings before teeing off? A basketball player bouncing the ball before shooting for the hoop?

Unlike cameras and lenses and apertures and shutter speeds, there’s no science to this. You can’t measure it or grade it on a scale, it’s just something you sense when you enter that state of “flow”.

It is (demonstrably) harder to define and explain than apertures and focal lengths, which is possibly why you can find a thousand online forums where photographers eagerly discuss the technicalities of gear but relatively few conversations about the zen-like quest for the “decisive moment”.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

It would be rude of me to mention the “decisive moment” without a nod in the direction of the man who coined the expression.

I was doing some research for a magazine article and was reminded of this old gem.

The 1998 documentary, “Pen, Brush and Cameras’ about Cartier-Bresson includes this segment where Eve Arnold talks about watching the Henri at work.

“He moves with great speed, he sees instantaneously, and he does a sort of little ballet, like a little dance. He rises on his toes, the camera goes to the eye, the click comes, and you don’t even know you’ve been photographed.” — Eve Arnold speaking about Henri Cartier-Bresson

Isn’t that moment when Henri is on tiptoes just exquisite?

“Pen, Brush and Camera” is available to watch on YouTube. The quality isn’t great but the content makes up for it.

A Final Word

“I work from awkwardness. By that I mean I don’t like to arrange things. If I stand in front of something, instead of arranging it, I arrange myself.” — Diane Arbus

If you’ve read this far you’ll appreciate that, like Diane Arbus, I too work from awkwardness.

Trying to find the right words to describe something intangible, yet essential, is not straightforward. So I was reassured to find these words in Steve Simon’s Passionate Photographer book:

“There is a mystery and magic to the creative process that can’t always be articulated.

[Photography] is a bit like a dance. We move around the floor trying new angles to see what they look like so we can arrive at the best possible place to take the picture.

This compositional dance is a game of inches. I maintain that you need to be looking through the viewfinder to see how a slight movement can dramatically impact your final composition. This is important to know, because a slight shift of camera position can make a world of difference.”

Next week

In next Friday’s newsletter we’ll get back to the nitty-gritty of building a consistent digital workflow. But I do hope that if you have a camera in your hand this week (and if not, why not?), you will give yourself permission to take more photos of fewer things. And should you be inclined to emulate Cartier-Bresson with a little tiptoe dance, you will have my admiration. Throw in a pirouette too. Why not? Dance, dance, dance.

Resources from this edition:

The Passionate Photographer by Steve Simon

I’d like less nitty gritty and more posts like this. You have something unique to say, let the others do the how-to posts.