Beyond the Frame 22/

Searching for sisters after an earthquake in Nepal PLUS how to optimise Lightroom Classic for maximum efficiency.

Bhaktapur

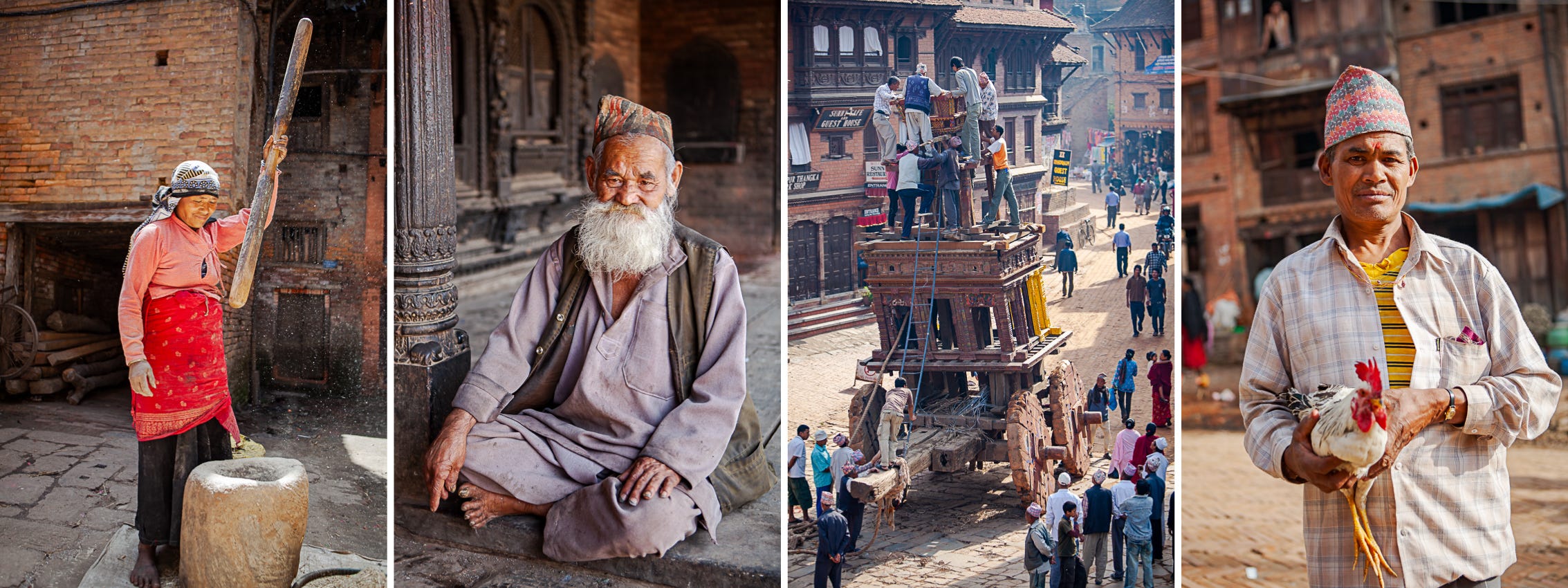

Whenever I’m in Nepal, I try to visit Bhaktapur. The city sits squarely in the foot of the Kathmandu valley, a dusty 15 kilometres from the capital. Bhaktapur is a thousand years old and I’m struggling to find a description that doesn’t include the phrase “where time stands still” but…

The five-roof pagoda overlooking the main square is over 300 years old. Buildings look like they have been standing for centuries, the ubiquitous red bricks providing a consistent, monochrome backdrop for thousands of carnivals and colourful ceremonies.

The city’s maze of narrow streets and alleyways are ideal for those of us who don’t mind being aimlessly lost. What’s around the next corner? A woman pounding grain in a stone mortar? A white-bearded gentleman, custodian of an ancient temple? A group of men standing precariously upon a teetering wooden chariot? Perhaps a man offering to sell a chicken at a competitive price?

All of these and more.

I like to seek out aesthetically pleasing backgrounds and just sit. I’m very good at sitting. I’ll compose a frame, take some meter readings, adjust camera settings and then watch people going about their day. I’m hoping that serendipity will bring interesting characters into the scene but, if I’m not working, I’m content to just sit and appreciate the surroundings.

I found an alleyway where a sliver of sunlight was shining zigzag highlights. Ideal backlighting.

So I sat.

And I focussed my attention on appreciating my surroundings. 😁

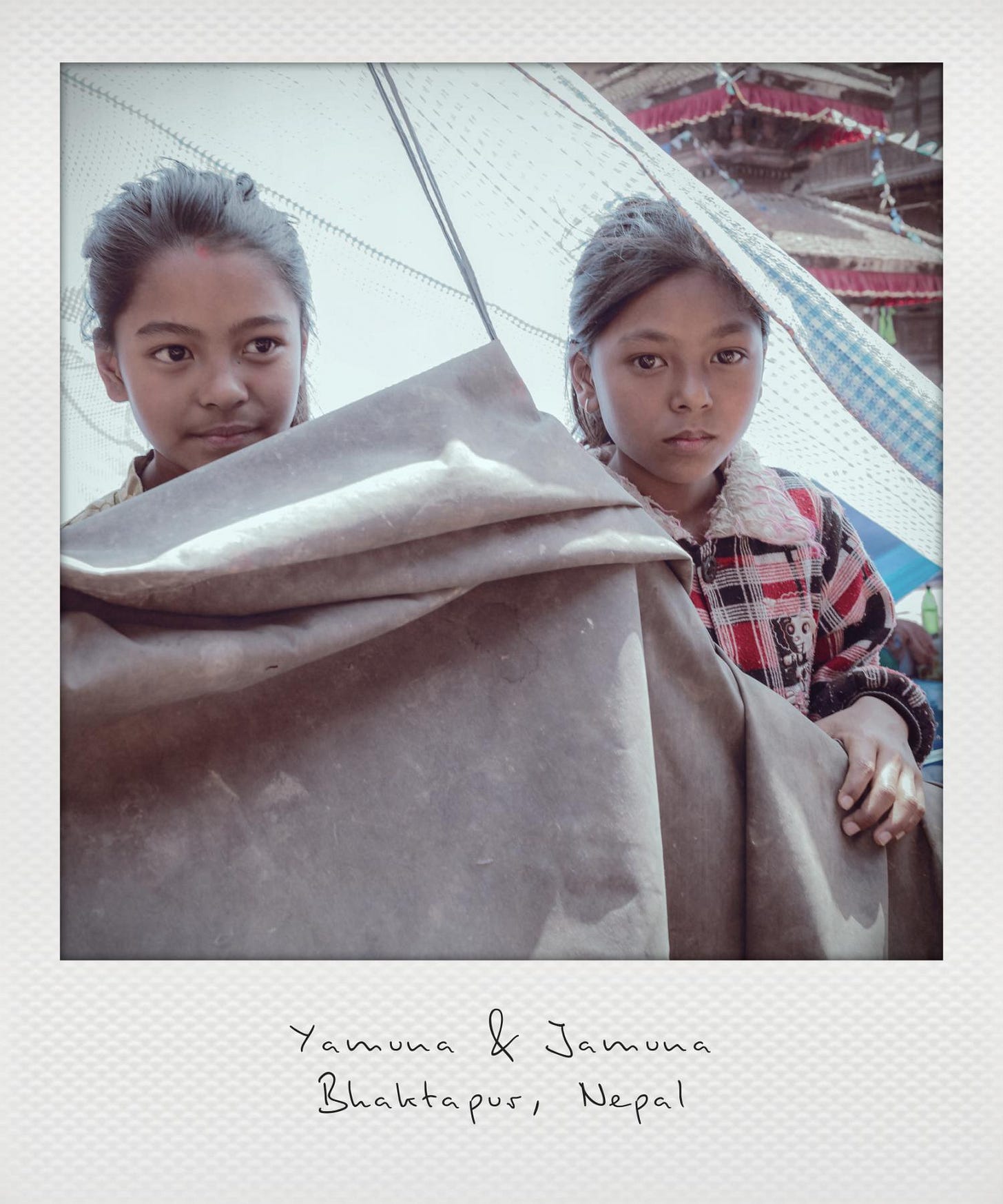

After a while, two girls sauntered into the alley, swinging their schoolbags. Half-way along the alley they stopped, one walked back to where I was sitting and asked, “Where are you from?”

We chatted, I asked if I could make some photos, which piqued her sister’s interest enough to prompt her to walk back too.

They told me their names, “Yamuna and Jamuna” and, very proudly, that they were twin sisters, five years old. They asked lots of questions. “What is your name? Do you speak Nepali? Do you have a sister? Do you have a wife? Can we have your camera?”

“My name is Gavin.”

“No.”

“Yes.”

“Yes.”

“How much?”

When they felt satisfied that I’d answered all their questions and were convinced that I was unlikely to give them my camera, they turned and strolled back up the alley, swinging their bags again.

And then they were gone.

I recorded their names in a notebook. I try to make prints if I’m likely to return to a place. A print is a simple and inexpensive but greatly appreciated gift. Even if I didn’t meet Yamuna and Jamuna again, chances are I’d be able to hand the prints to a friend or neighbour. It’s a very small gesture but I hope it goes some way to adjusting the potential imbalance of “taking” photographs.

You might have noticed that I never use the phrase “take photos” in the newsletter. I prefer “make photos”. I also try to avoid “Shoot”, “Grab” and “Capture”. So much of the language of photography suggests something predatory. I’m under no illusions, there is an inescapable imbalance, but I try very hard to approach my work, especially street portraits, with a sense of respectful collaboration. No doubt we’ll return to this topic!

But before I digress too far, let me take you back a few moments. As Yamuna and Jamuna were walking away down the alleyway, they did something that I’ve noticed people doing 99 times out of 100.

They gave a backward glance over their shoulders. In fact, they stopped walking and turned.

The final glance

I’ve seen this happen so often that I’m prepared for it now. I have dozens of photos of people I’ve spoken with giving a backward glance as they walk away.

I’m not sure why we do it. If there are any psychologists reading, please let me know what’s happening.

My theory is that as we walk away, we’re reviewing the conversation in our minds, cementing the memory, like re-watching a video recording of our encounter on fast-forward. Perhaps we attach a mental image to that recording for future reference? When we glance back, we’re confirming and fixing that mental image.

Whatever the reason, it’s a characteristic so universally common that I can now accurately predict exactly when somebody will glance back.

I hoped that Yamuna and Jamuna might turn at the point where they reached the sunlight. And that’s exactly what they did. The sunlight shone through their pigtails, casting their shadowed outlines on the pavement.

It isn’t a photo likely to win any awards but it delights me, which, after all, is why we make photographs, right?

The portrait of Yamuna at the top of this edition appeared in my first exhibition at London’s Photographers’ Gallery, which made me even more determined to return to Bhaktapur with some decent prints to share.

However, the circumstances of my subsequent search for Yamuna and Jamuna took an unexpected and deadly turn.

After the Earthquake

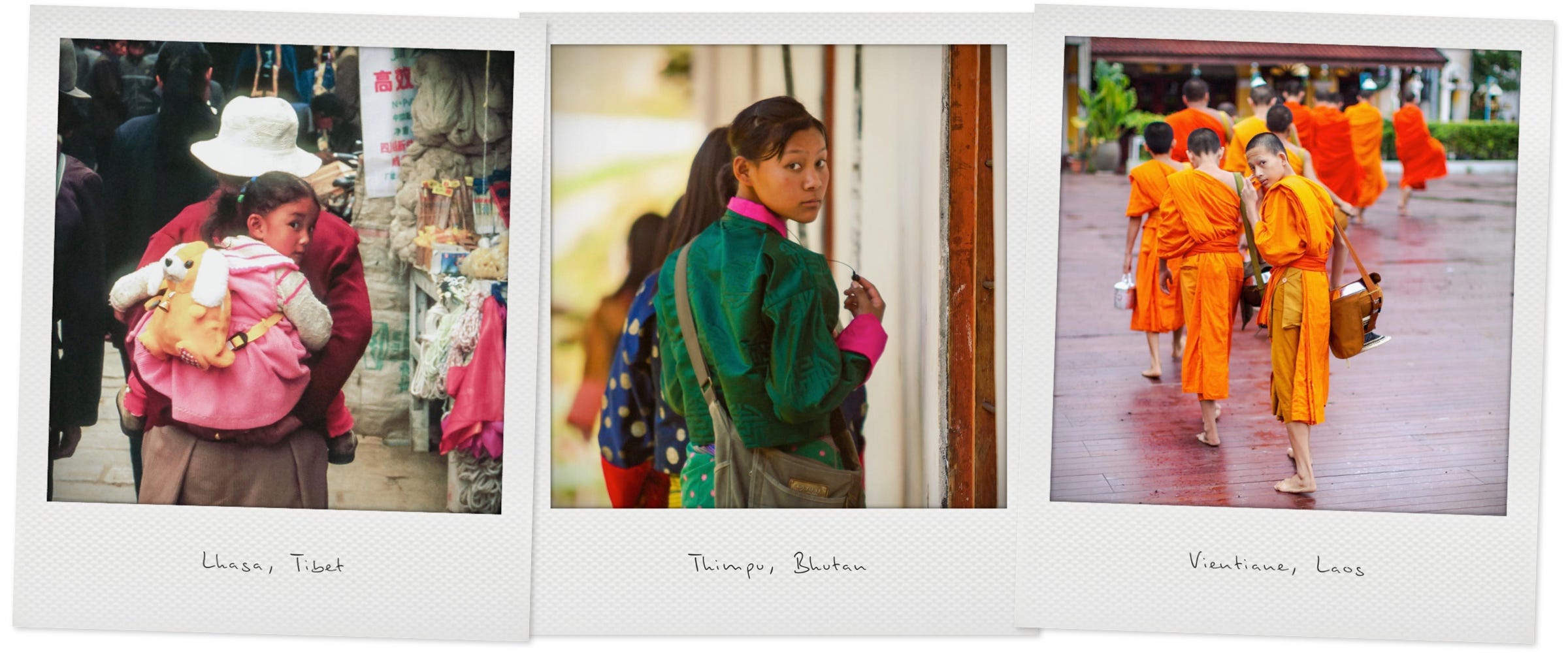

I arrived in Kathmandu one day after the devastating earthquake in April, 2015. This is the caption that accompanied images I wired back to news editors.

“KATHMANDU, NEPAL - APRIL 25: A major 7.8 earthquake hit Kathmandu mid-day on Saturday, and was followed by multiple aftershocks that triggered avalanches on Mt. Everest, burying mountain climbers in their base camps. Many houses, buildings and temples in the capital were destroyed during the earthquake, leaving over 6000 dead and many more trapped under the debris as emergency rescue workers attempt to clear debris and find survivors. Regular aftershocks have hampered recovery missions as locals, officials and aid workers attempt to recover bodies from the rubble.”

The death toll was later revised to 8,962. Many thousands were badly injured and many, many more were left homeless.

Searching for the sisters

Bhaktapur was very badly affected. The ancient homes and temples were not built to withstand such a force. Had the earthquake not happened at midday, when many people were outside their homes, the loss of life would have been far greater.

In Bhaktapur, I found people removing rubble by hand, desperately searching for missing friends and family.

I found the alleyway where I had previously sat on a sunny day, casually watching passersby, and where I answered Yamuna’s and Jamuna’s many questions. One building had collapsed, most were visibly unsafe. Rubble piled so high that it covered motorbikes — you might be able to see the saddle and handlebars of a moped, still upright, in the bottom right of the frame.

The chances of surviving beneath a pile of rubble like that are slim. Slimmest of all for children.

I found many people sheltering under plastic sheets, their homes either reduced to rubble or dangerously unsafe. I showed my photos of Yamuna and Jamuna, asking if anybody knew what had happened to them…

Yamuna and Jamuna were 11 years old when the earthquake struck Nepal. I didn’t know if anybody would recognise them from my photos, now six years out of date.

Of course, in a place like this where everybody knows their neighbours and community is a way of life, the girls were quickly identified.

“Yes! Yamuna and Jamuna. They are safe. They are here. Come with me.”

A man took me by the hand and led me down the rubble-strewn street.

Beneath a sheet of blue plastic, beside a few meagre belongings, I was reintroduced to Yamuna and Jamuna.

Their house at the end of the alley had been reduced to a shell but, thankfully, they had been outside when the interior collapsed. They led me back into the alley and we stepped over the front door, which was lying on the ground. Although the walls were standing, the two storey interior had fallen, leaving a pile of wood and brick, through which fragments of clothing and pieces of cutlery were poking.

We did not stay long. I hurried them out, fearing an after-shock. The tremors continued to reverberate for days after the initial earthquake.

Standing in the alley, with the sun in almost exactly the same position as it had been six years before, I made three quick photos to serve as a comparison with the photos we’d made on our first meeting.

To say I was relieved to find the girls safe and well is an understatement. Many were not so fortunate.

However, their situation was still precarious. Now homeless, like so many others, they relied upon the charity of friends and neighbours. Their parents had gone to stay with an uncle, trying to protect the family’s few remaining possessions.

I was at least able to make sure they had food and clean water. It felt incredibly inadequate.

Update

I returned to Nepal every year after the earthquake, getting updates from their neighbours. The family relocated to the countryside, the girls reunited with their parents. I haven’t seen them since but know they are 20 years-old now, they’ve finished school and started work.

Back when they were five, their long list of questions did not include, “Where do you think we’ll be in 15 years?” But if they’d asked, I’d have been content to have been able to reply, with great certainty, “Safe.”

Optimising Lightroom Classic

Be prepared now for a handbrake-turn in tone as we move from the sublime to the… well, not ridiculous… let’s just call it a shift of gear to something practical.

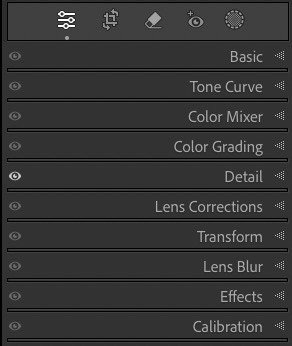

This is a quick guide to optimising your processing workflow in Lightroom’s Develop module. It’s good for Camera Raw too.

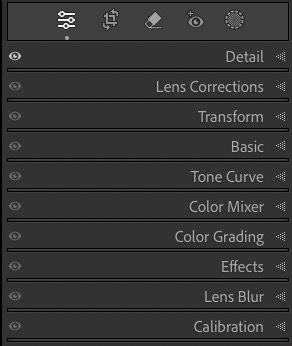

You probably won’t be surprised to learn that Adobe has a recommended Order of Operations for the Develop module. This is the sequence we follow when processing images to avoid what they describe as, “Poor performance and unexpected results” — A phrase I last heard after my High School exams.

You may, however, be surprised to learn that the adjustment panels in Lightroom’s Develop module do not follow Adobe’s recommended path. A design decision that I for one would like to ask them about!

Luckily for you, I’ve done my homework (better late than never) and have a solution.

Adobe’s Recommended Order of Operations

Denoise

Content-Aware Remove/Heal/Spot

Lens Profile Corrections (CA and Profile, if available)

Profile

Global Adjustments

Local Adjustments

Go to Lightroom, look at the adjustment sections. Notice anything? Unless you’ve already changed the order, you’ll see Denoise, the first in Adobe’s recommended list, is found inside the Detail panel, fifth from the top. Why isn’t it at the top?

Global exposure adjustments are found in the top Basic section but near the bottom of the recommended sequence. It’s not helpful.

To follow Adobe’s recommendation, this sequence of adjustment sections makes more sense:

Reordering the sequence is straightforward.

Right-click anywhere in that panel

Select “Customise Develop Panel…”

Drag the sections into the order shown below

Click “Save” and relaunch Lightroom

Now, when processing, you can begin at the top with the Detail section, apply Denoise or manual noise reduction if you need to, then move down the sections, following the recommended path.

The Basic panel has moved down, which might take some getting used to, but it’s now in the correct place in the sequence.

Presets

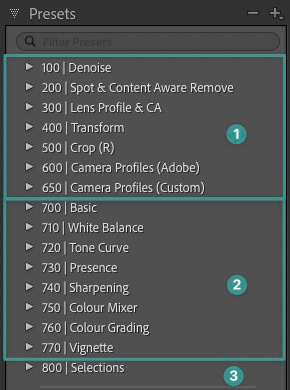

You can organise Presets in the same fashion. This is my list, below.

I’ll be sharing all of my custom presets with you in the coming weeks so you’ll be able to replicate my workflow and adjust/improve as you wish.

The first four items in Adobe’s recommended sequence, which I like to think of as building the foundations.

Global adjustments. Exposure, White Balance, Tone Curves, Colour shifts etc.

Local adjustments. Masks and whatnot.

Summary

Adobe’s recommended sequence for processing makes a lot of sense. Even though Lightroom processing is “non-destructive” there are certain things you’d want to do before diving in to the detail.

For example, there’s little point in making exposure and tone adjustments before you apply noise reduction. That way madness lies.

Having the correct sequence in the right-hand panel provides an easy-to-follow, step-by-step workflow.

Better yet, organising presets to reflect the same sequence means you’ll be set up to process photos more consistently and in half the time.

Now relax, safe in the knowledge that you are no longer at risk of “poor performance and unexpected results”.

That’s all for this week. If you have any comments, questions, feedback or suggestions, I’m ready and waiting.

I say I’m ready and waiting but I’m typing this at my Standing Desk and have a nagging pain that feels suspiciously similar to when I had a kidney stone. That affliction resulted in four painful days in hospital with Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy and Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy. I’ve no idea what they are either but it stung.

Mrs. G., ever the pragmatist, says I probably ate too much Brie.

Tune in next week to discover what happens next.

Until then, enjoy your photography and go well.

Love the story and documenting of the sisters. How wonderful would it be if you were to meet up with them again someday.

Never thought of backward glances before. What a great observation.