Beyond the Frame 11/

How still images can show the passing of time, Keanu Reeves, Marmite, Hedonic Adaptation and the dark arts of people who sketch.

Still images, we know, preserve moments in time. That’s their appeal. Photographs remind us how something looked at a particular time in a particular place. They breathe life into moments lost to the past.

Photographs say, “Hey! This is how this thing/person/animal/sunset/street/tree/flower looked for 1/500th of a second at one specific point in history.”

Photographs can be magical time-portals, sending fading echoes of the emotions we felt as we peered into the viewfinder and made the shutter go “THZZCK”.

Like you, I’d guess, I find it interesting to look back at old family photographs but my reaction to them has changed over the years. The photographs are the same. It’s me who’s changed, thankfully. Such is life.

Viewing a collection of these tiny slivers of time recorded over weeks, months or years can enhance our sense of time passing. For example, I’m fascinated by time-lapse films where fractions of a moment are sliced together, shrinking hours into minutes.

My time-lapse film of Bangkok’s Chao Phraya river condenses the “Blue Hour” into the “Blue Three Seconds” and sunset, which is already brief at this latitude, flashes overhead in the blink of an eye.

For the past five years I’ve taken a self-portrait at 11am each day (with the Close-up app). The resulting video is a startling (and unpublishable) reminder of how, regardless of how much of my wife’s anti-ageing cream I secretly acquire, I am undeniably ageing. (Confusingly, my wife does not appear to be ageing at anything like the same rate. I suspect she keeps the genuine anti-ageing cream well hidden.)

So, in yet another example of how Hollywood legend Keanu Reeves and I are virtually indistinguishable (apparently he has a new book out and has been thinking about mortality a lot), I’m increasingly fascinated by representations of time passing.

A father and daughter chronicle

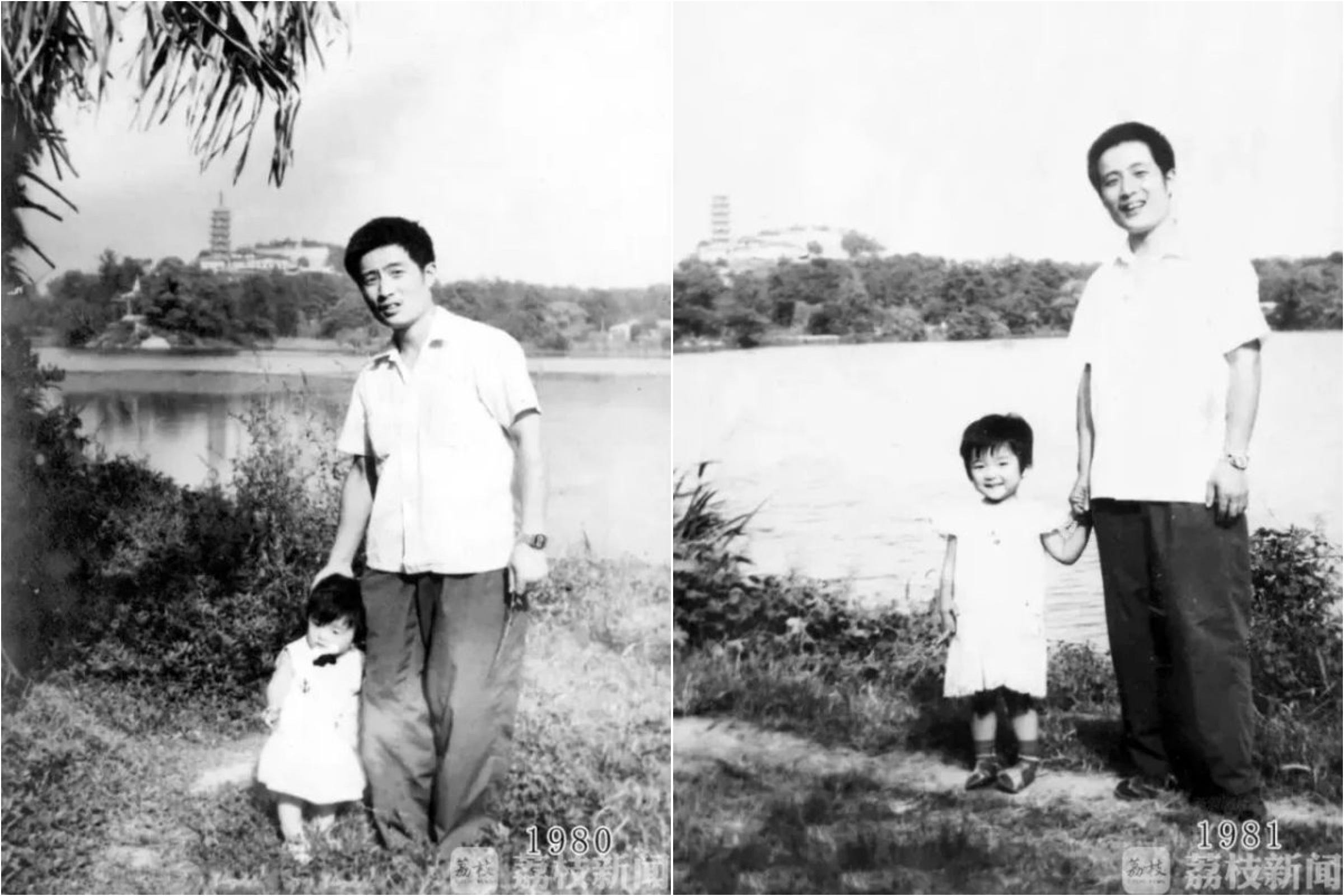

26 year old Hua Yunqing wasn’t thinking about the passage of time in 1980 when he asked his wife to take a photo of him and their one year old daughter, Huahua.

“Our family of three went to a friend’s house near Yiquan. When I passed by the shadow lake, I saw the Jinshan pagoda behind me and felt that the background was good, so I wanted to take a picture with my daughter.”

One year later, Hua Yunqing was swimming in the lake and remembered the location. He took a second photo with his daughter.

“After the photo was developed, compared with a year ago, the appearance of our daughter has changed significantly. This was so meaningful!”

Year after year, Hua and Huahua have returned to the lakeside spot. Sometimes friends or relatives accompany them and make their portrait and sometimes they use the camera’s self-timer.

The photographs have changed from black & white to colour. Huahua has grown, married and had children of her own. Although she now lives in Japan, she returns to China every year for the family photo, in which Hua’s grandchildren now also appear.

If you watch the video closely, you’ll see their 1998 photo appears to be missing. Huahua was studying in Japan and unable to return to China. Hua asked his daughter to send a photo from Japan, which he Photoshopped into a picture of himself by the lake, so as not to break the annual tradition.

You can see their 1998 photograph in this article.

Even though there are now presumably just 44 photographs in Hua’s photo album, I find the storytelling power in that small handful of lovingly-made images to be profound. If my calculations are correct, assuming the photos were each made at 1/60th of a second, the total time represented by all of Hua’s 44 photos is about two-thirds of one second. Two-thirds of a second that represent the 555 million seconds lived by Hua and his daughter since 1980.

It makes me wonder if we don’t have far too many photos. Perhaps 44 might be sufficient?

You can also see Hua and Huahua’s photographic chronicle here.

Eve and Me

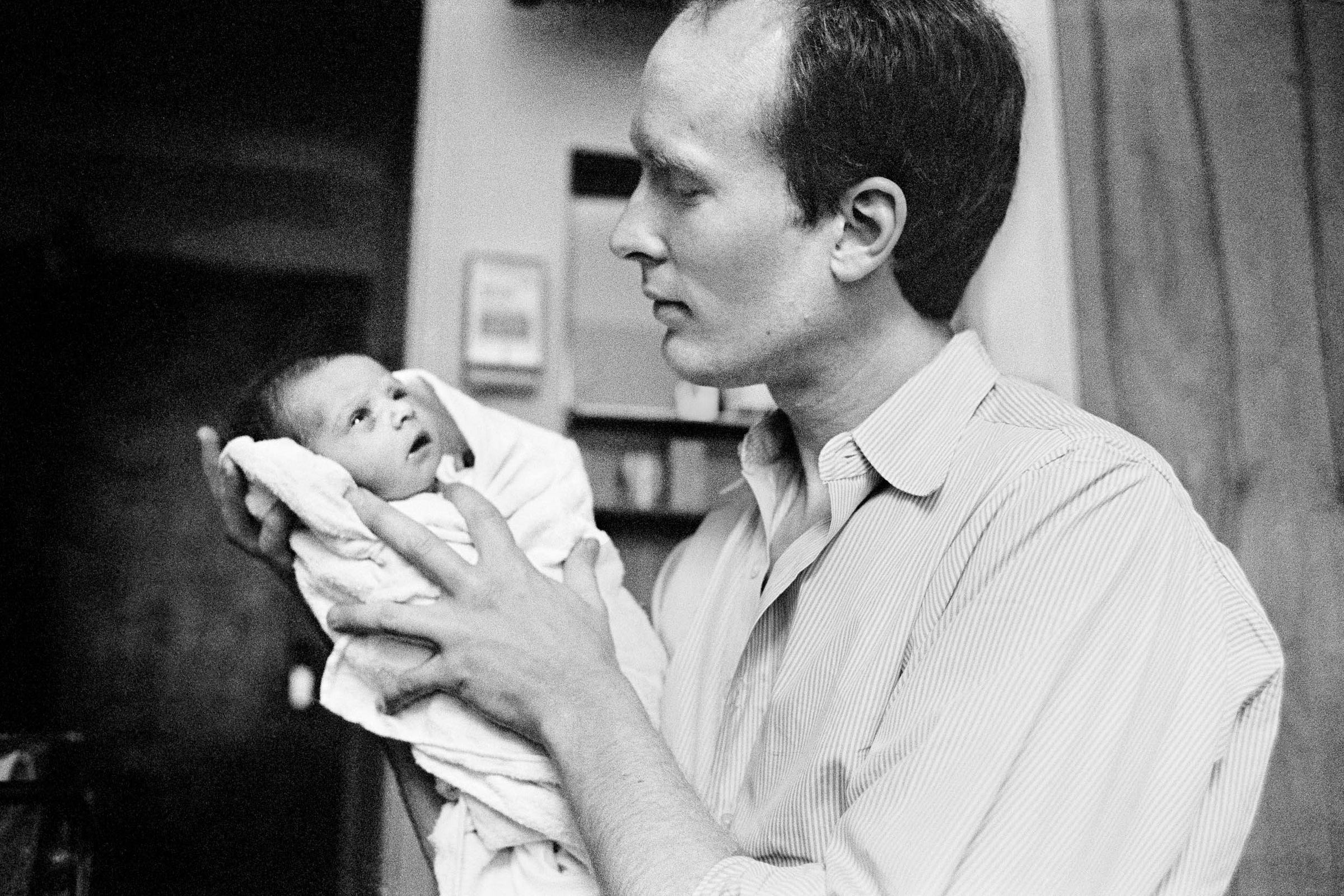

Similarly, Geoffrey Biddle’s chronicle of father/daughter portraits, Eve and Me, shares a series of photographs made over many years.

The project begins with Eve’s birth in 1982 and ends in 2004, after the death from cancer of Geoffrey’s wife and Eve’s mother, the artist Mary Ann Unger.

“Eve and Me traverses their closest years, from city playgrounds to country fields, without and within the shadow of illness and loss.”

“When we went to the country place, we took the same walks, lit the same fires, and cooked the same meals, but it was so different without Mom. Her presence was everywhere.”

You can purchase a copy of Eve and Me and enjoy Geoffrey’s other projects on his website.

I’m grateful to have found both of these time-travelling photographic stories, bittersweet though they may be. I often feel like it would be helpful if we could slow time down. The best things are often gone too soon. Sunrises, lunch with friends, hot-air balloon rides, analogue photography, candy floss, summer, Mark Hollis, Jeff Buckley, Jack Kurtz, raspberry pavlova, clean kitchen worktops, perfect eyesight, uncomplaining joints, jars of Marmite, youth…

If this reminder of how rapidly life is whizzing past has left you feeling a little melancholy, let me respond in two ways:

Splendid! My work here is done.

The charming Hannah Fry’s explanation of Hedonic Adaptation will reassure you that you’ll soon revert to your baseline level of happiness.

If you’ve worked on or know about a photographic project that covers an extended period of time in this way, I would love to hear about it. And if you think it sounds like an interesting idea but wish you’d began a project 20 years ago, I sympathise. But start today. I promise that 20 years from now, you’ll be pleased that you did.

Magical Mystery

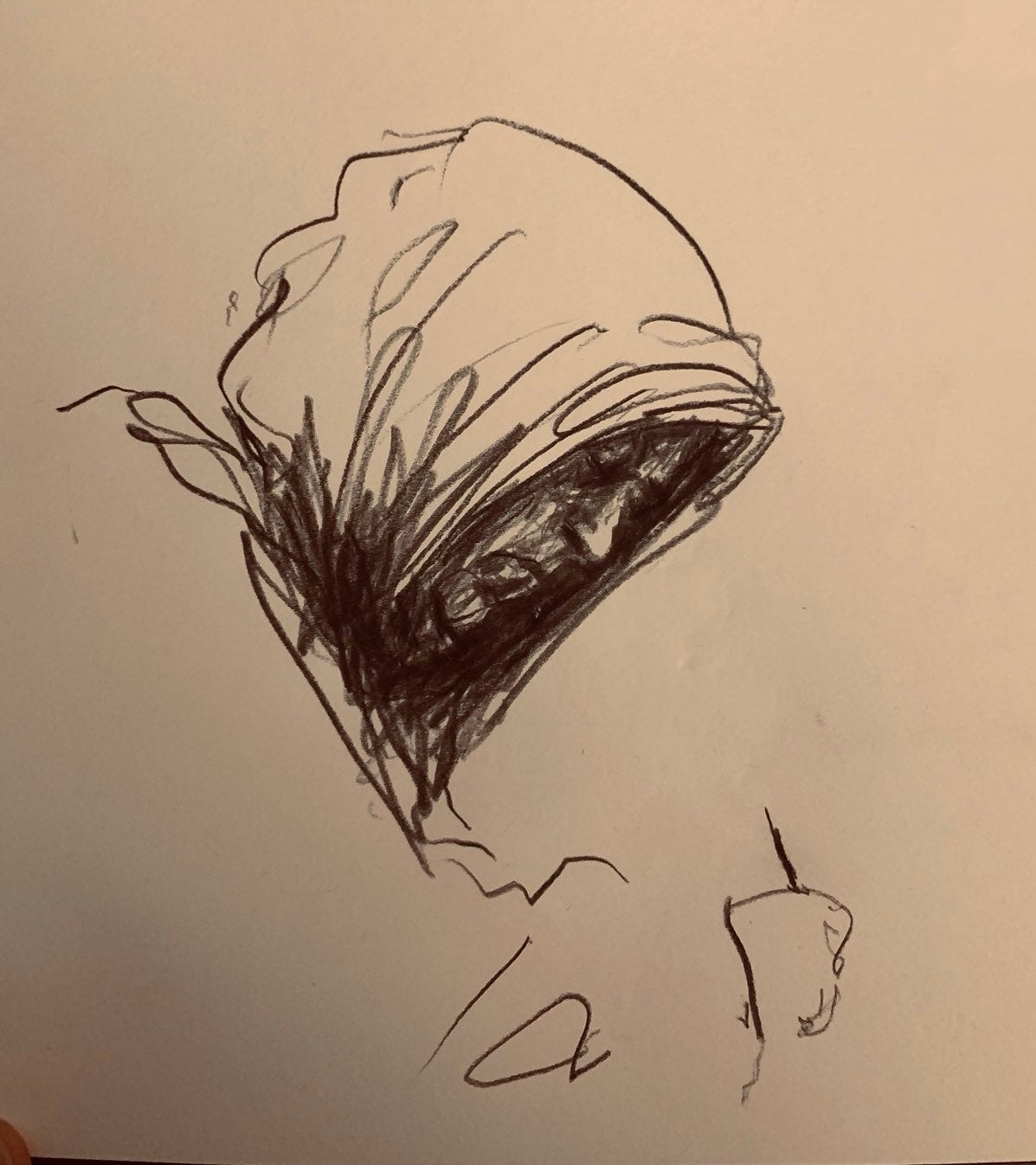

Finally — and largely unrelated to photography — I’ve been cleansing my Twitter timeline of political nonsense and replacing it with more uplifting art (there are loads of inspiring artists on Twitter — who knew?) and I found this beautiful sketch.

I would be grateful if somebody could explain to me, in terms a child would understand, how this is possible?

To say I’m envious of artists who can quickly scribble a few apparently random lines and yet bring something like this to life would be a massive understatement.

I’ve been staring at it for 20 minutes — probably much longer than it took Monsieur Pierre to draw it — looking at individual pencil strokes, trying to understand how the lines and circles, which by themselves are meaningless, combine to create something that’s instantly recognisable.

It remains a mystery. I fear it will always remain a mystery. Perhaps it’s a left-brain/right-brain thing and my grey matter is too stubbornly hard-wired into order and logic.

So instead of trying to deconstruct the sketch in the hope of understanding the process, I’ve returned to simply enjoying the impressive sketches on Monsieur Pierre’s timeline and consoling myself with the firm belief that Peter would be equally jealous of the military precision with which I organise my sock drawer, “How does he do it?” Swings and roundabouts.

PS Peter’s on Instagram too.

If you follow any excellent artists on Twitter (I refuse to call it X and so should you), please share a link. If I’m going to “do” any social media, I’d prefer it to be uplifting.

“These are the good days.”